The 14th European Nutrition Conference (FENS) took place in November in Belgrade, and we were there to cover and share with you some insightful topics.

Oliver Witard from the School of Basic & Medical Biosciences at King’s College, London, UK, delved into the topic of “Taking a Food-First Approach to Protein Recommendations: The Matrix Effect.”

“Taking a Food-First Approach to Protein Recommendations: The Matrix Effect”, briefly:

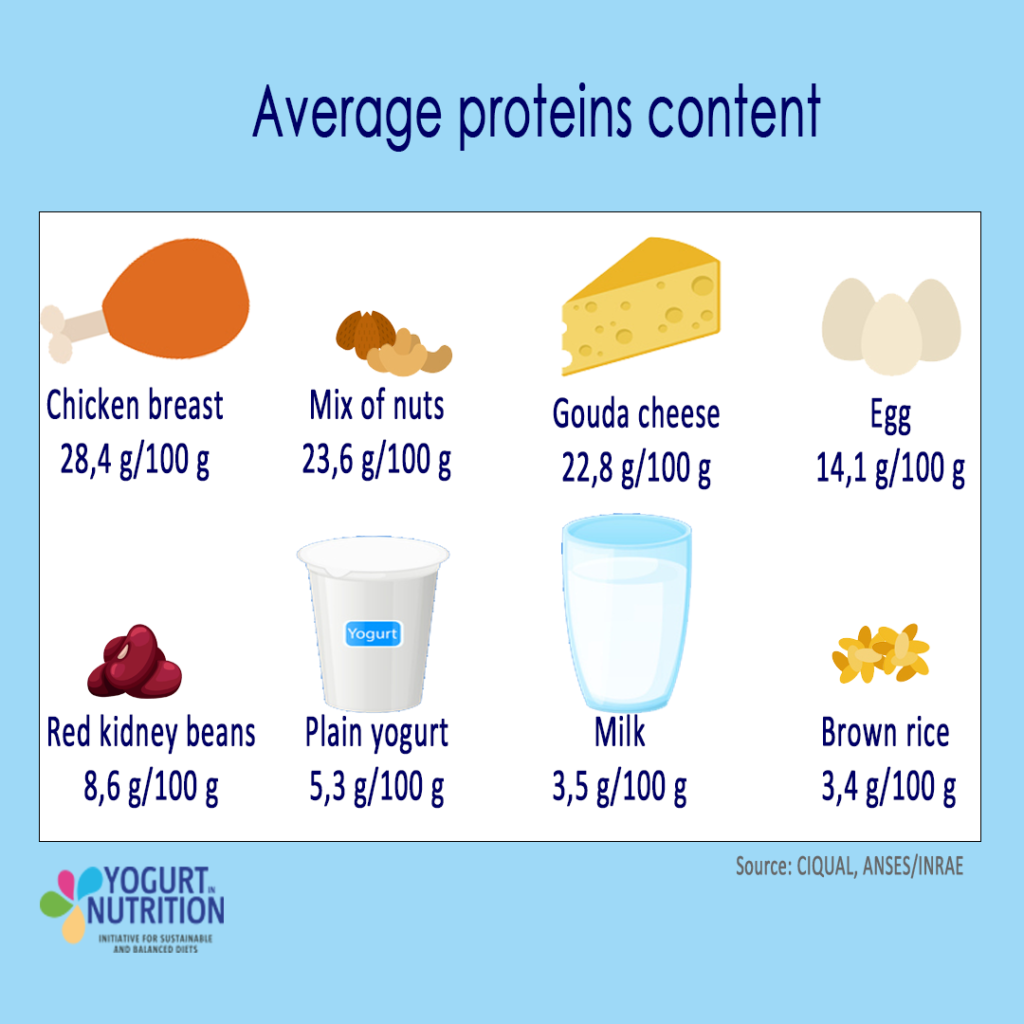

Muscle protein synthesis (MPS) is vital for building and repairing muscle proteins. Recommended protein intake for maximizing MPS is around 0.24g/kg in each meal in young adults and 0.40g/kg bodyweight in older adults (1).

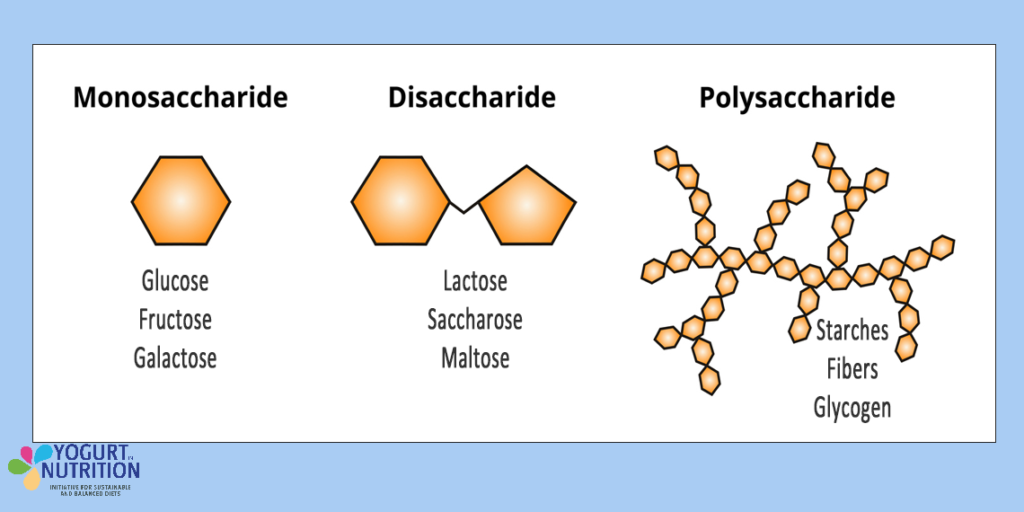

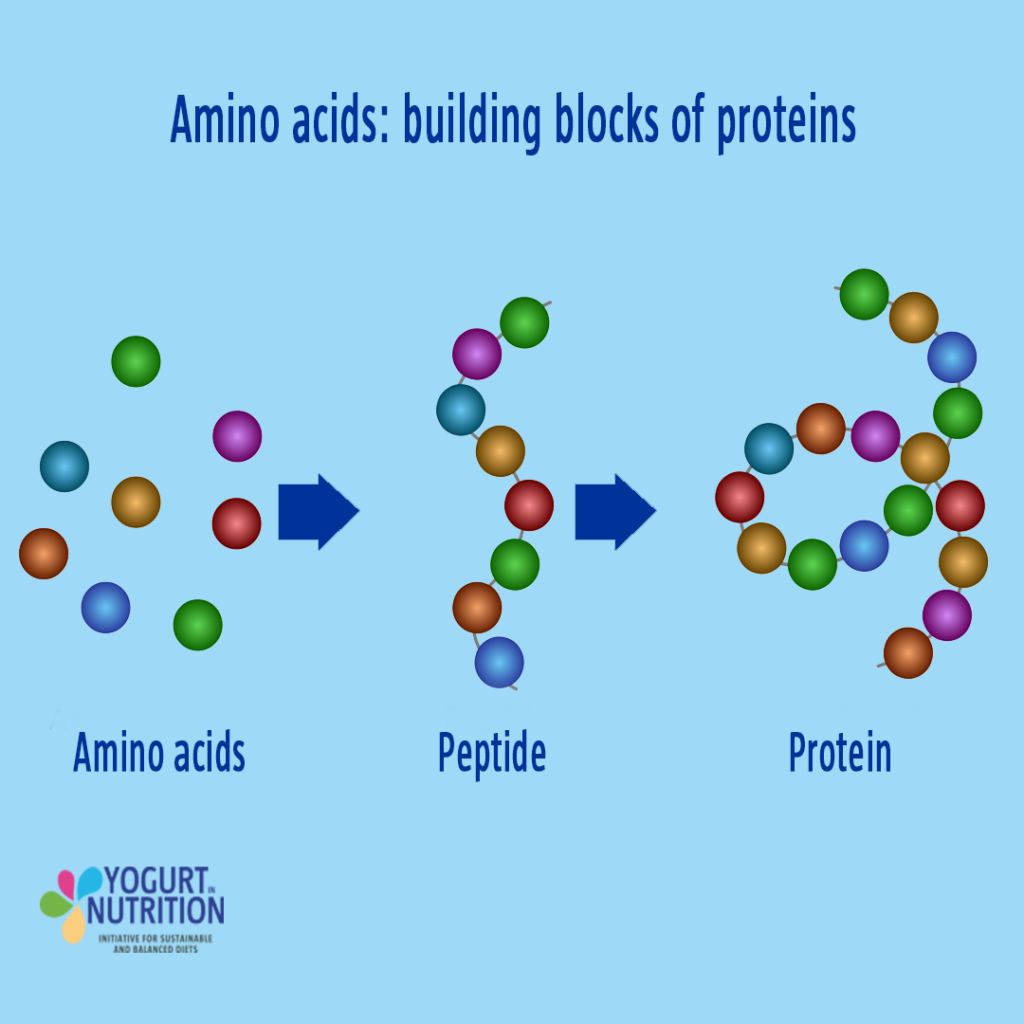

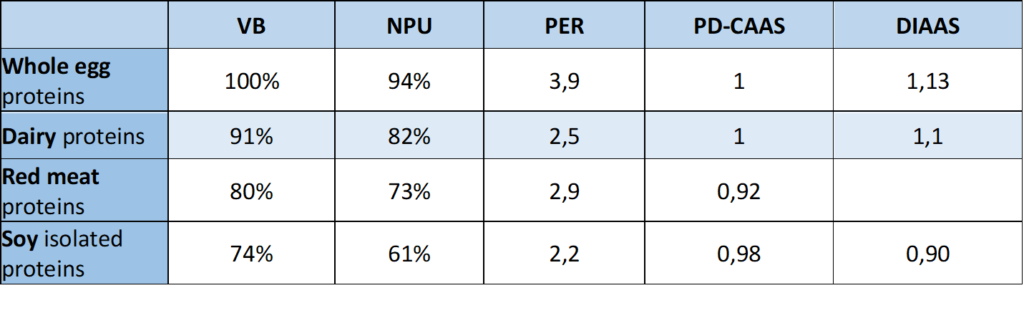

MPS is triggered by amino acids via protein intake, particularly during the postprandial period and exercise recovery. The “leucine trigger” hypothesis suggests that leucine is the primary stimulus for MPS (2). Studies (3,4) looking at the effect of isolated protein sources consumption (casein, whey and soy protein) on MPS support this hypothesis: whey protein consumption leads to a rapid rise in blood leucine concentration as compared to other protein sources, and a consequently greater postprandial MPS.

However, recent studies using whole food protein challenge this notion. In a study (5) comparing skimmed milk and beef ingestion during exercise recovery, skimmed milk showed a greater MPS response than minced beef, despite the latter leading to a quicker leucine appearance in the blood. The improved MPS with skimmed milk may be attributed to the food matrix effect, where interactions between nutrients and non-nutrient components would impact protein digestion and amino acid absorption rates.

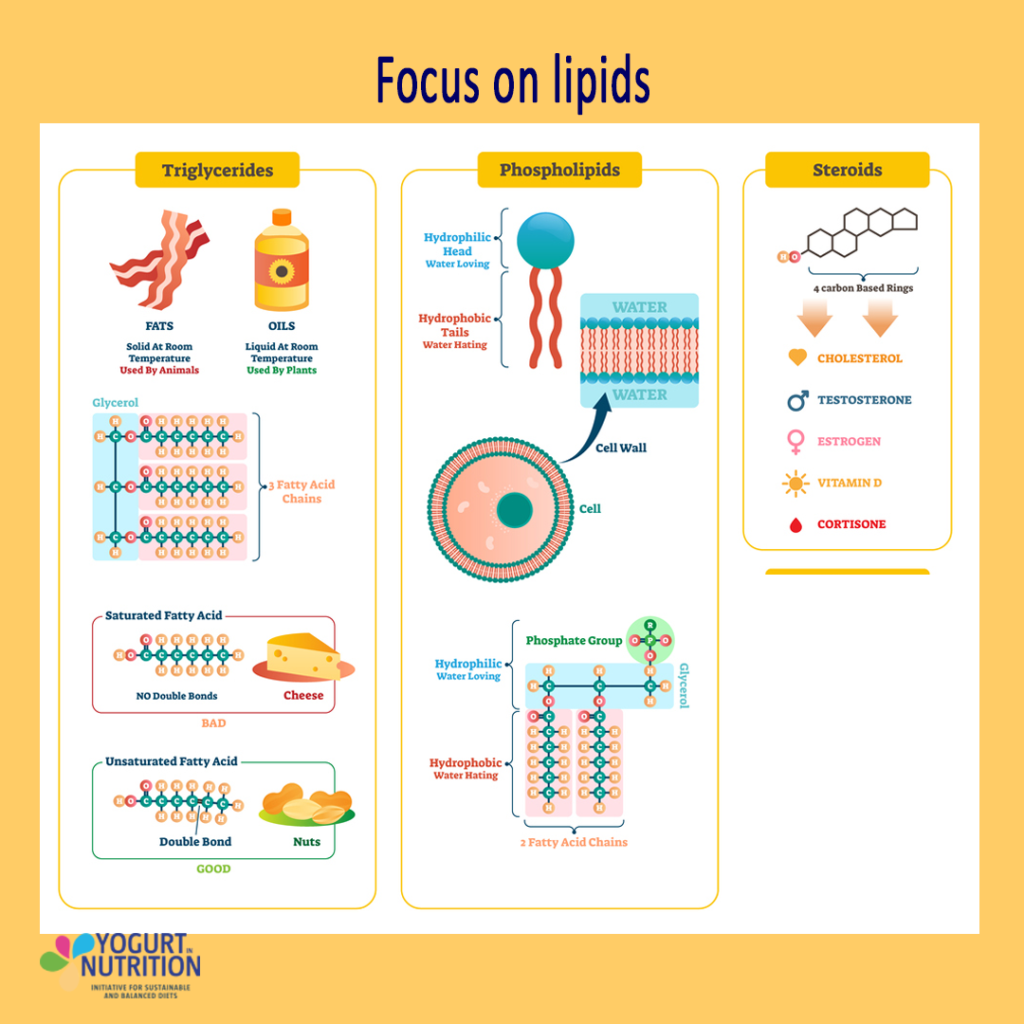

The food matrix effect is highlighted in several studies. Whole milk (which is richer in fats) lead to a greater amino acid utilization during exercise recovery than skimmed milk (that contains no fat), emphasizing the potential influence of fat and protein interaction (6). Similar findings were observed with raw eggs (containing a fat-rich yolk) compared to egg whites alone, suggesting a positive impact of fats on MPS (7). Additionally, glycation (meaning the attachment of sugars to the milk proteins) in milk powder hindered postprandial amino acid availability, especially lysine, which might be due to the interaction of sugars and proteins (8).

Given that protein recommendations are based on isolated protein sources, revisiting them to incorporate the food matrix effect may be necessary to optimize MPS, especially in the context of exercise recovery.

Key Messages :

- The ingestion of protein-dense whole foods stimulate a robust MPS response despite eliciting a slower rise in leucine availability during exercise recovery.

Thus, the “leucine trigger” hypothesis may be more relevant after the ingestion of isolated protein sources rather than the consumption of whole food protein sources

- The food matrix effect i.e.the ingestion of whole foods and the associated (non)nutrient-nutrient interactions, facilitates a greater MPS response than the individual actions from each individual nutrient

- A paradigm shift is needed in human nutrition to re-define protein recommendations based on commonly consumed protein-rich food

Sources:

(1) Moore DR, Churchward-Venne TA, Witard O, Breen L, Burd NA, Tipton KD, Phillips SM. Protein ingestion to stimulate myofibrillar protein synthesis requires greater relative protein intakes in healthy older versus younger men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015 Jan;70(1):57-62. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu103. Epub 2014 Jul 23. PMID: 25056502.

(2) Zaromskyte G, Prokopidis K, Ioannidis T, Tipton KD, Witard OC. Evaluating the Leucine Trigger Hypothesis to Explain the Post-prandial Regulation of Muscle Protein Synthesis in Young and Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Front Nutr. 2021 Jul 8;8:685165. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.685165. PMID: 34307436; PMCID: PMC8295465.

(3) Burd NA, Beals JW, Martinez IG, Salvador AF, Skinner SK. Food-First Approach to Enhance the Regulation of Post-exercise Skeletal Muscle Protein Synthesis and Remodeling. Sports Med. 2019 Feb;49(Suppl 1):59-68. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-1009-y. PMID: 30671904; PMCID: PMC6445816.

(4) Tang JE, Moore DR, Kujbida GW, Tarnopolsky MA, Phillips SM. Ingestion of whey hydrolysate, casein, or soy protein isolate: effects on mixed muscle protein synthesis at rest and following resistance exercise in young men. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009 Sep;107(3):987-92. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00076.2009. Epub 2009 Jul 9. PMID: 19589961.

(5) Burd NA, Gorissen SH, van Vliet S, Snijders T, van Loon LJ. Differences in postprandial protein handling after beef compared with milk ingestion during postexercise recovery: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Oct;102(4):828-36. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.103184. Epub 2015 Sep 9. PMID: 26354539.

(6) Elliot TA, Cree MG, Sanford AP, Wolfe RR, Tipton KD. Milk ingestion stimulates net muscle protein synthesis following resistance exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006 Apr;38(4):667-74. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000210190.64458.25. PMID: 16679981.

(7) van Vliet S, Shy EL, Abou Sawan S, Beals JW, West DW, Skinner SK, Ulanov AV, Li Z, Paluska SA, Parsons CM, Moore DR, Burd NA. Consumption of whole eggs promotes greater stimulation of postexercise muscle protein synthesis than consumption of isonitrogenous amounts of egg whites in young men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017 Dec;106(6):1401-1412. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.117.159855. Epub 2017 Oct 4. PMID: 28978542.

(8) Nyakayiru J, van Lieshout GAA, Trommelen J, van Kranenburg J, Verdijk LB, Bragt MCE, van Loon LJC. The glycation level of milk protein strongly modulates post-prandial lysine availability in humans. Br J Nutr. 2020 Mar 14;123(5):545-552. doi: 10.1017/S0007114519002927. Epub 2019 Nov 15. PMID: 31727194; PMCID: PMC7015880.

Learn more with Oliver Witard

Hello, can you introduce yourself?

Oliver Witard: My name is Oliver Witard, and I am a Senior Lecturer in Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism at King’s College London in the UK.

What does the Food Matrix bring to the topic when studying exercise metabolism?

Oliver Witard: When we talk about the Food Matrix, we’re talking about the application of protein nutrition as opposed to mechanisms that underpin the response of muscle to protein-derived amino acids.

Historically, studies looked at the response of the muscle to individual amino acids or isolated intact proteins. And those studies were set up for a good reason, because they enabled us to understand what was happening, the mechanisms of action. Why is it that perhaps one protein source stimulates the muscle greater than another protein source? They had a really strong place within protein nutrition and have advanced our understanding.

The concept of the matrix effect allows us to offer more applied information. By studying the muscle’s response to commonly consumed protein foods, we can provide practical recommendations since people consume food, not isolated nutrients. This approach may not contribute significantly to mechanistic understanding, but it proves invaluable for applied perspectives, shaping more relevant dietary advice.

What does this change for athletes, for example, for sportspeople? Is that going to change their approach to their protein intake?

Oliver Witard: It might not drastically alter their approach, but it will bring more information and knowledge. The UK Institute of Sport, for example, adopts a “food-first” approach in their nutritional recommendations, emphasizing the essential role of food before considering supplements.

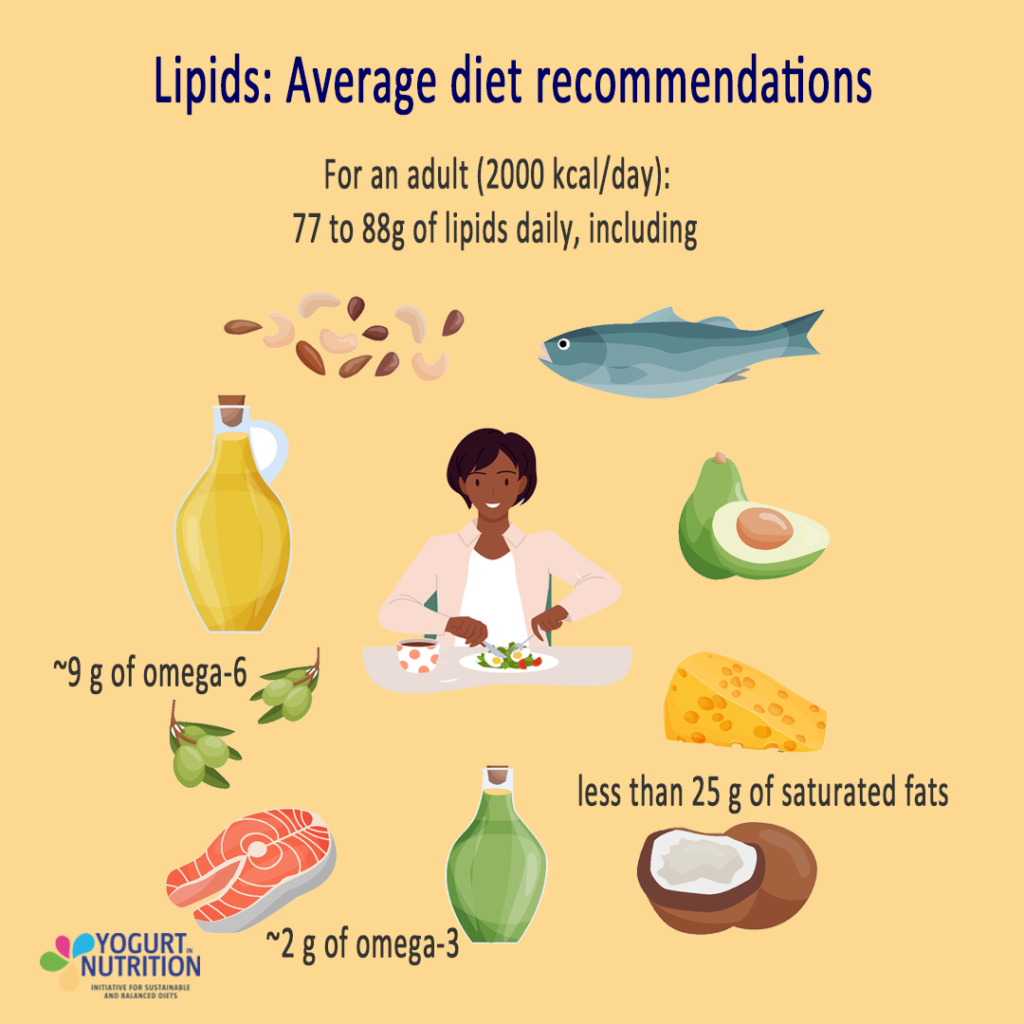

Athletes need a solid food foundation before considering additional supplements like protein supplements, creatine, or omega-3s.

While it might not change the guidelines, this perspective underscores the interest of prioritizing whole foods in nutritional recommendations.

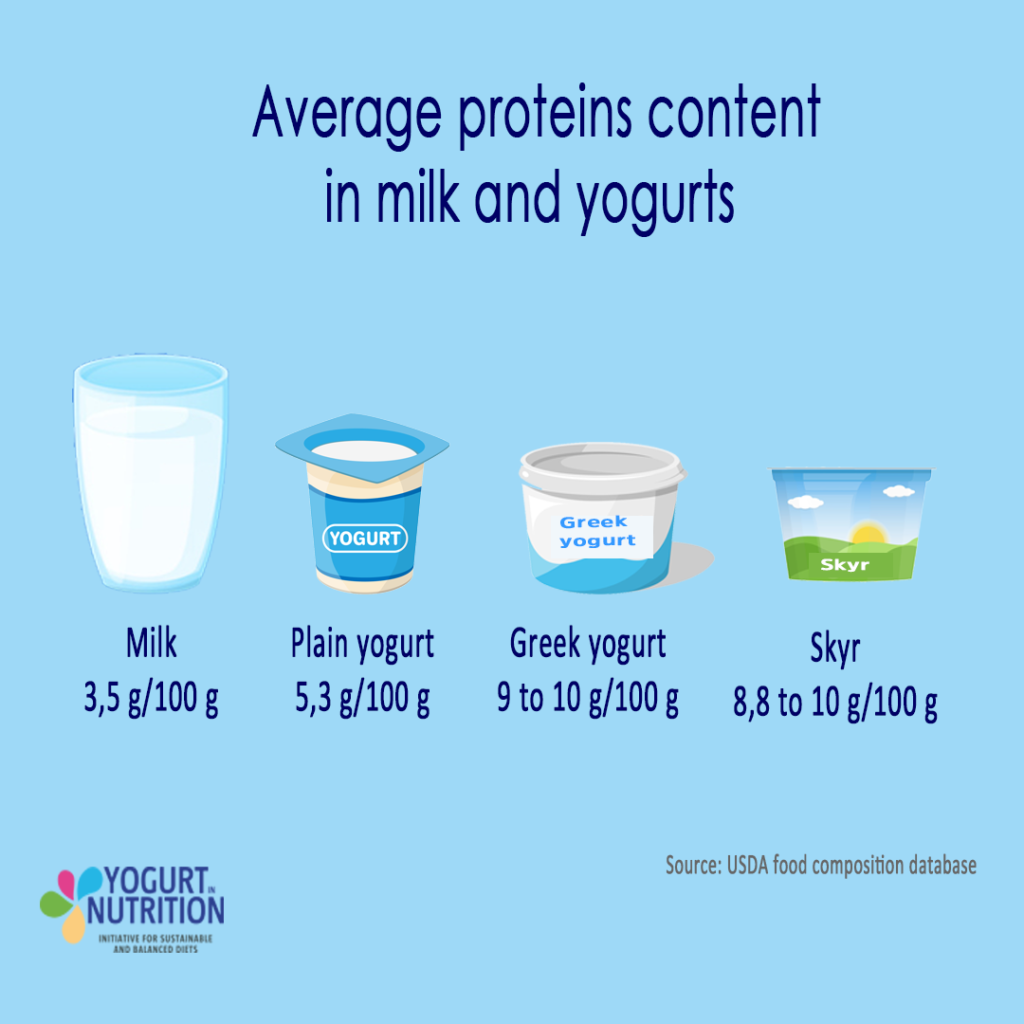

As dairy, yogurt, or skyr are known for their protein content. How do they fit into this food approach? What is your opinion on protein from dairy products?

Oliver Witard. A Dutch intervention study with quark showed that both in young and older adults, the consumption of quark, results in a robust stimulation of muscle protein synthesis.

There’s no reason to believe that other forms of proteins, of yogurts, won’t also stimulate a robust increase in protein synthesis, given the protein content alongside other nutritional profiles of yogurts. Personally, I find yogurt to be an excellent source of protein and believe there’s much more to explore regarding its protein supply.

To go further, in the context of weight loss, there’s a notable study from McMaster University by Andrea Josse, showing promising results in terms of body composition and bone mineral density with yogurt consumption. It underscores the importance of considering the body composition rather than focusing solely on weight reduction.

To conclude, what would be the key messages from your presentation today?

Oliver Witard: Our current understanding of protein recommendations primarily stems from studies on isolated proteins or free amino acid sources rather than commonly consumed food sources.

Exploring how these recommendations hold up when applied to everyday protein foods is an area worth investigating.

The Matrix effect is intriguing, suggesting interactions between nutrients. Studies with milk protein, eggs, and omega-3s indicate a growing body of evidence supporting a matrix effect in stimulating protein synthesis.

Dr Oliver Witard is a senior Lecturer in Exercise Metabolism & Nutrition at the King’s College, London, UK. His research focus is healthy ageing. He is interested in understanding the physiology that underpins why we lose muscle mass and quality with age. His research also explores the role of exercise and novel nutritional interventions – primarily protein nutrition – to offset age-related perturbations in muscle metabolism. He has extensive expertise in stable isotopic tracer methodology for measuring in vivo muscle protein turnover in humans. He also applies these techniques to athletic populations to optimize training adaptations, body composition and performance.

Nutritional requirements for proteins

Nutritional requirements for proteins