Lactose

Lactose

Lactose

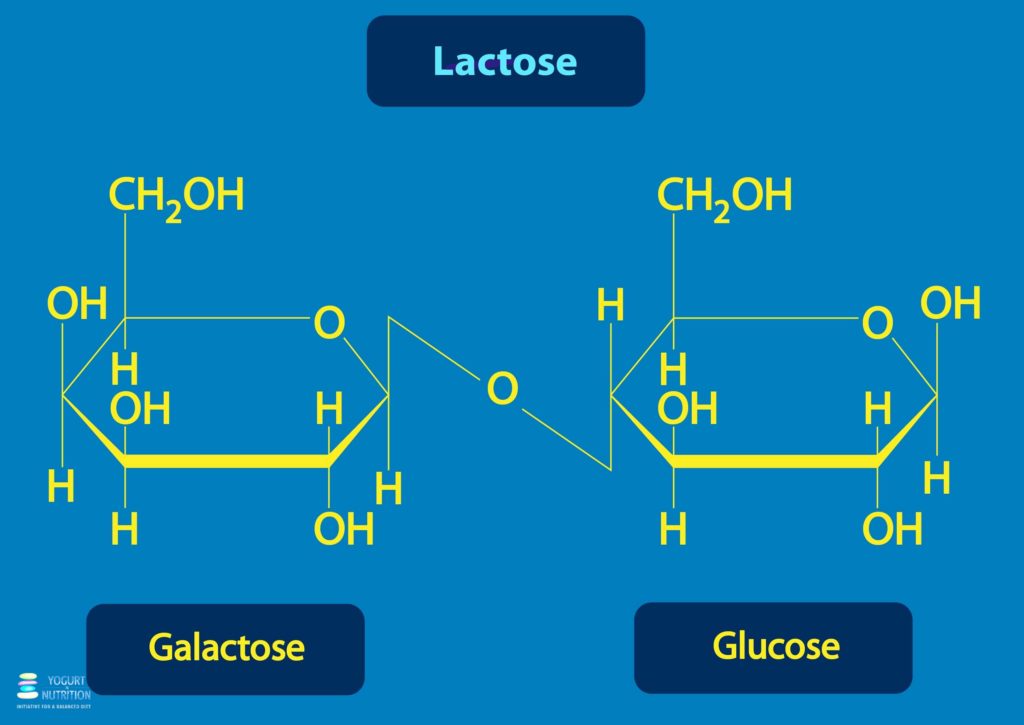

What is lactose?

The lactose is a carbohydrate (“sugar”) exclusively found in milk and dairy products. It is a disaccharide, composed of galactose and glucose.

The lactose is the main sugar of milk and dairy products:

- Regular milk (sheep, cow or goat) contains almost 12g of lactose per 1 cup of 250ml

- Yogurt contains 5 g of lactose per 1 portion of yogurt (125g or 4,4oz)

- In cheeses, there are only traces of lactose.

Breast milk has the highest concentration of lactose (main carbohydrate of breast milk) and is essential for brain growth and development of all mammals.

This is why, from birth, the baby produces, a specific enzyme in the small intestine, the lactase, which is able to digest the lactose and split it into two molecules: the glucose and the galactose.

Glucose, which can be also found in many types of foods, is the main source of energy for the body.

Galactose, which is only available naturally, in the lactose, will be metabolized and be the component of several molecules, such as cerebrosides, gangliosides and mucoproteins, serving various biological functions (neurological, muscular or immunological, among others). The galactose will be also one of the component of the molecules that determine ABO blood types in blood cells.

Lactose is an essential nutrient during childhood (that can be tolerated even during adulthood)

Lactose is an essential carbohydrates during early childhood and it provides the main energy for child development during the first months of life.

Some elements of comparison:

- human milk contains 7.2% lactose (= 50% of the infant’s energy requirements)

- cow’s milk contains only 4.7% lactose (= 30% of the infant’s energy requirements).

The lactase activity is therefore maximum at birth but it decreases over the years and notably, it decreases progressively after weaning to reach less than 10% of level before weaning.

This is a normal phenomenon, called lactase non-persistence. However, the level of decline may vary among individuals.

In some populations, the decline of the lactase activity is more pronounced. It is the case among people of Asian, African, South American, Southern European and Australian Aboriginal descent.

However, in some populations who consume regularly dairy products even during adulthood, the lactase activity remains. It is mostly the case in Northern Europe.

Note that due to lactase non-persistence, adults can have difficulties to digest milk beyond a certain amount (a bowl) but can continue to take milk in small amounts or included in recipes. On the other hand, cheeses and fermented milks (yogurts) are very well tolerated.

What about not digested lactose?

In case of reduced lactase activity, some of the consumed lactose from dairy products will not be digested in the small intestine and will be used as a nutrient by the gut microbiota (the microorganism population living in the digestive tract).

In the colon, bacteria produce their own lactase and can digest the lactose. It will result in the production of short chain fatty acids (acetate, propionate, butyrate) and gases (hydrogen, carbon dioxide, methane). Short chain fatty acids will serve locally as energy provider for the gut microbiome or be absorbed and transported to the liver for their metabolization.

Undigested lactose (as well as other milk carbohydrates) will contribute to promote the growth of bifidobacteria, a health-positive genus of bacteria present in the gut microbiome. Therefore the lactose act as a prebiotic, encouraging the growth of beneficial bacteria for health. As with aging, there is a reduction in bifidobacteria, as well as markers of the immune function, the lactose can play an interesting life-long role in countering the aging-associated decline of some immune functions.

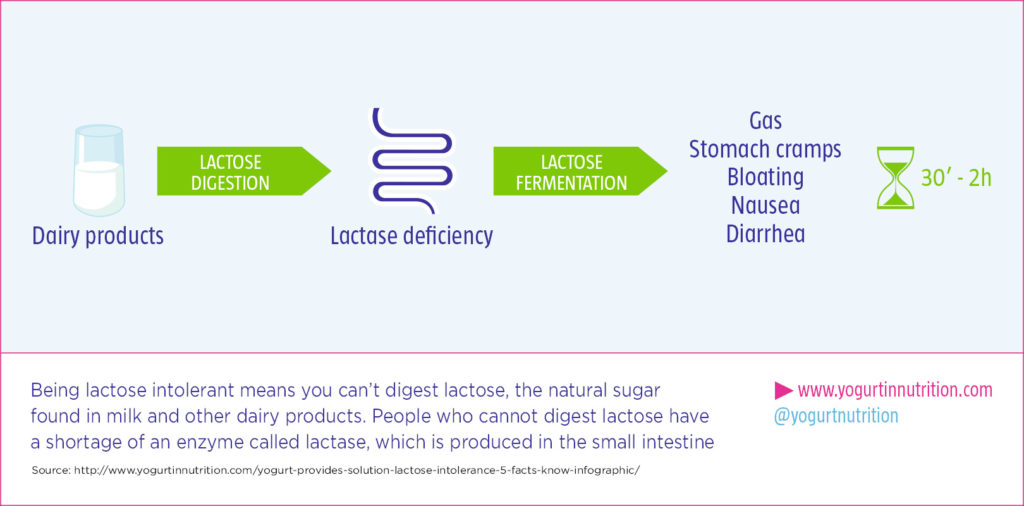

However, for some individuals, this bacterial fermentation of lactose produces gas and may increase the gut transit time and intracolonic pressure, resulting in one or many symptoms such as bloating, diarrhea or flatulence. This is what we call lactose intolerance. It is a lactose maldigestion that results in one or many digestive symptoms.

For most individuals, this lactose fermentation by the gut microbiome produces no or very few symptoms.

For more information and sources: