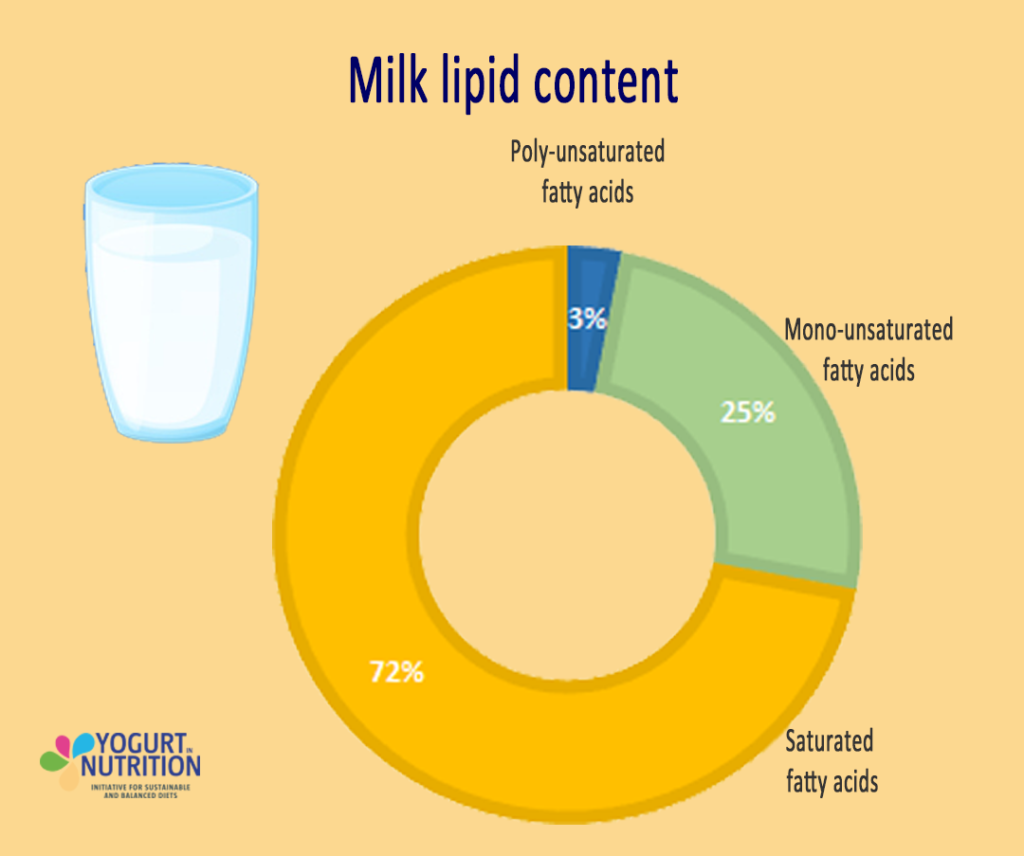

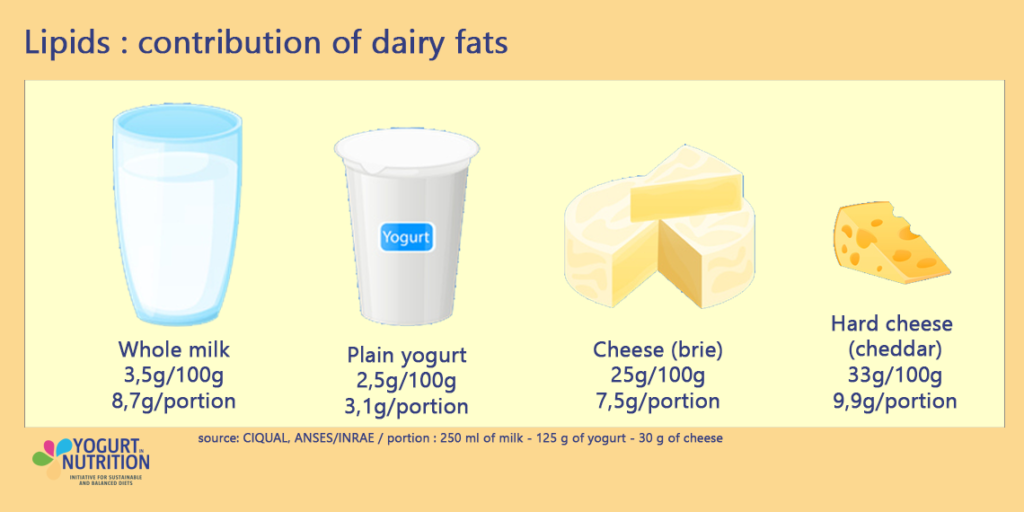

Yogurt contains both micronutrients – vitamins and minerals – and macronutrients, including proteins and fatty acids.

Yogurt contains high-quality protein, including all nine essential amino acids in the proportions needed for protein synthesis.

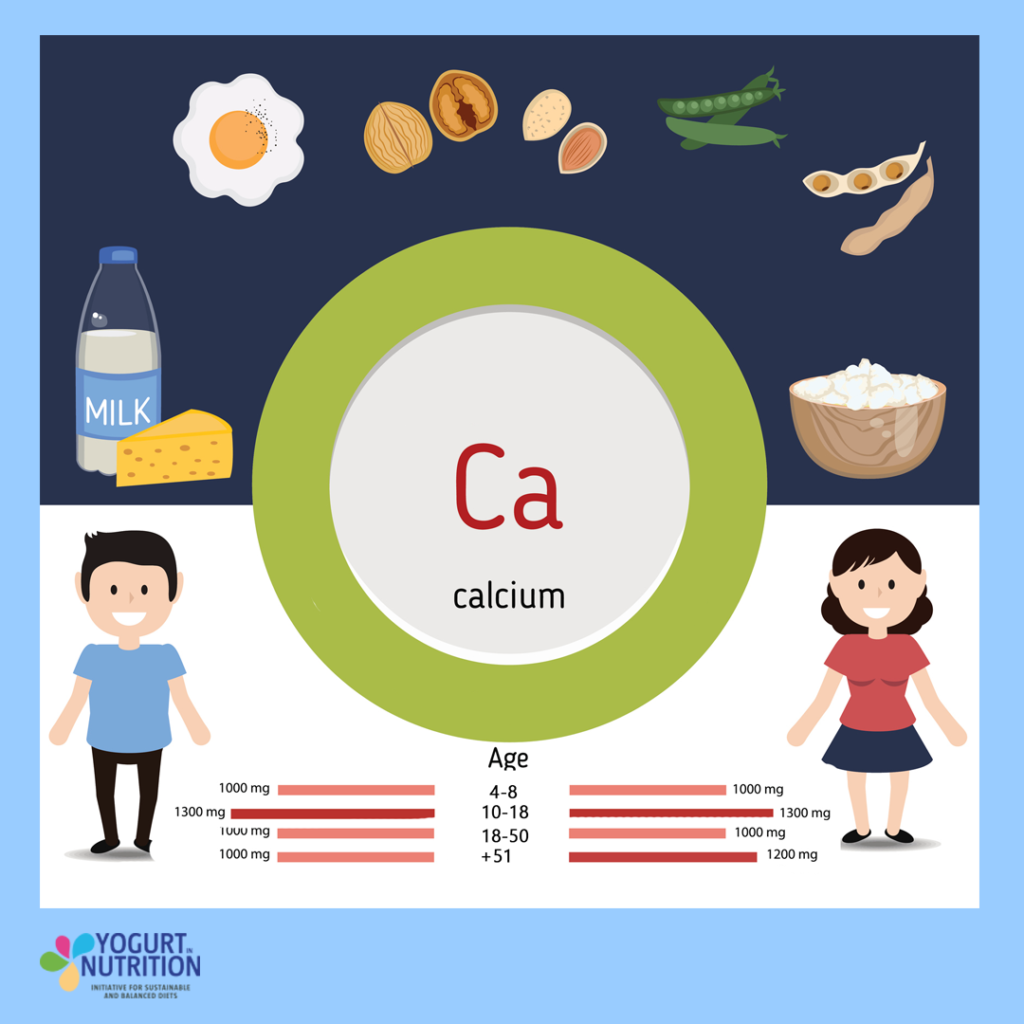

Yogurt is a rich source of calcium, providing up to 20% of daily calcium intake per 116 g or ~4-ounce portion (one average pot).

Yogurt also provides smaller amounts of many other micronutrients, including potassium, zinc, phosphorus, magnesium, iodine, vitamin A, riboflavin (vitamin B2), vitamin B5, vitamin B12 and in some countries, vitamin D.

Yogurt consumption helps meet nutrient intake requirements

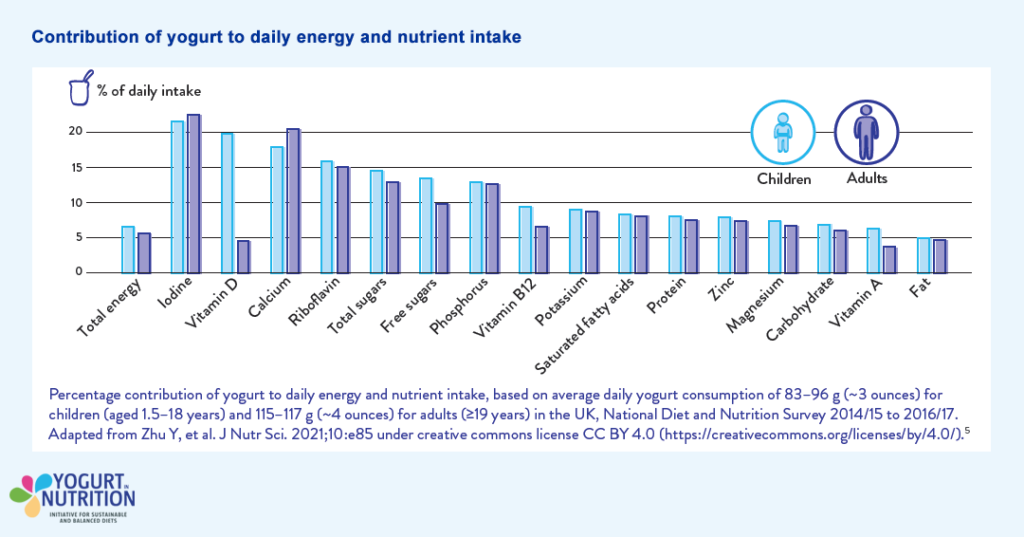

Yogurt and other dairy products contribute to key nutrient intakes for adults and children. That is why most regional and national food-based dietary guidelines recommend the consumption of dairy products – and, when amounts are specified, two or three servings per day are typically recommended.

Adults

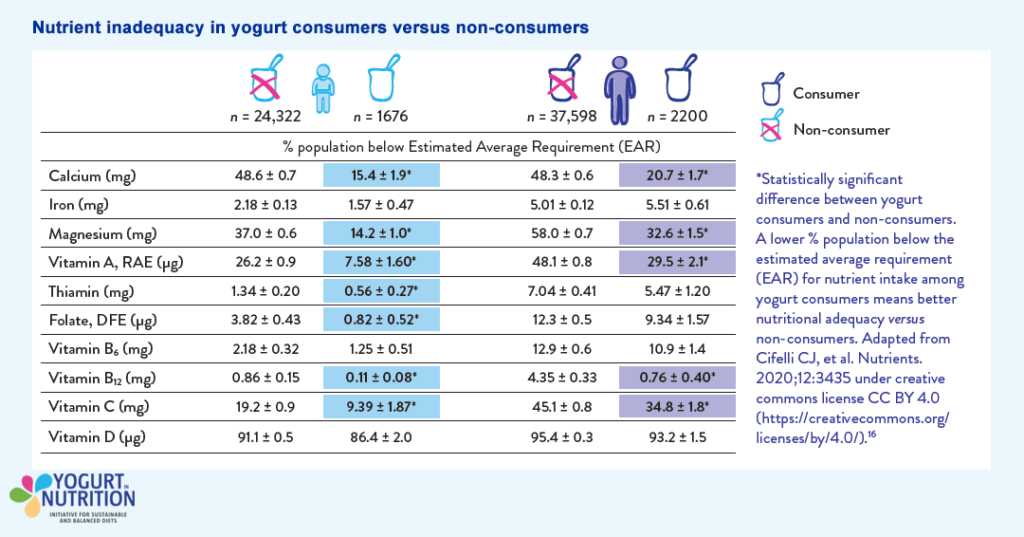

Many people fall short of meeting recommended intakes of certain nutrients in their diet. Close to 30% of men and 60% of women in the USA do not consume enough calcium and >90% do not consume enough vitamin D. Deficiencies of several nutrients persist in the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia including calcium, vitamins A, D, B12 and zinc.

Yogurt contributes many of these nutrients. For example, 125 g (~4 ounces) of plain yogurt provides, among other nutrients, 20% of an adult’s recommended daily intake of calcium, 21% of riboflavin, 11% of vitamin B12, and 16% of phosphorus.

Data from the USA National Health Nutrition and Examination Survey (NHANES), the Canadian Community Health Survey, and the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey show that yogurt consumers have higher daily intakes of several key nutrients including riboflavin, vitamin C, folate, vitamin D, potassium, iron, magnesium and calcium.

Furthermore, regular yogurt eaters are more likely to meet or exceed nutrient recommendations for vitamins and minerals including vitamin A, riboflavin, folate, potassium, calcium, magnesium, zinc and iodine

“Yogurt is a nutrient-dense food containing a wide range of macro and micro-nutrients. Eating yogurt every day can help us meet our recommended levels of several key nutrients.”

Children

Good diet quality is important for children and adolescents to support growth and development.

Teenagers are especially at risk of nutrient shortfall, and vitamin D, calcium, potassium, fibre and iron are of particular concern. Yogurt is a valuable part of a balanced nutrient-rich diet during childhood, contributing a substantial percentage of a child’s needs for micronutrients and macronutrients.

Data from the USA NHANES show that increasing dairy food consumption (milk, cheese and yogurt) to meet the recommended level in the USA for adolescents of three servings per day can make up for the shortfall of three nutrients of public health concern – calcium, vitamin D and potassium.

The UK survey data suggest that adding a 125 g (~4 ounces) pot of low-fat fruit yogurt per day to adolescents’ diets would increase mean calcium intake from below to above the Recommended Nutrient Intake.

Yogurt’s contribution to total and added sugar intake is relatively low

The World Health Organization recommends limiting the consumption of non-milk extrinsic sugars – which include those added to food by manufacturers or by consumers – to a maximum of 10% energy intake. However, many people in Western societies are exceeding this threshold.

Concerns that sweetened yogurt contributes to these excess sugar intakes are not supported by the scientific data. In the USA, a NHANES analysis found that flavoured yogurt contributes about 1% of added sugars to the diets of adults. This compared with 28.1% from soft drinks.

Added sugar intake increases throughout childhood and amounts to 15% of total daily energy intake among adolescents. While more than 50% of total sugars and 66% of added sugars in children’s diets come from sweet products such as cakes, sweets and sugary drinks, yogurt accounts for only 1–8% of total sugars and 4–9% of added sugar in children’s diets in Europe.

References:

- YINI Digest, Issue 1. November 2014. What added value does yogurt bring to dairy protein?

- Zhu Y, Jain N, Holschuh N, et al. Associations between frequency of yogurt consumption and nutrient intake and diet quality in the United Kingdom. J Nutr Sci. 2021;10:e85.

- Williams EB, Hooper B, Spiro A, et al. The contribution of yogurt to nutrient intakes across the life course. Nutr Bull. 2015;40:9–32.

- Keast DR, Hill Gallant KM, Albertson AM, et al. Associations between yogurt, dairy, calcium, and vitamin D intake and obesity among U.S. children aged 8–18 years: NHANES, 2005–2008. Nutrients. 2015;7:1577–93.

- Marette A, Picard-Deland E. Yogurt consumption and impact on health: focus on children and cardiometabolic risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:1243S–7S.

- Demmer E, Cifelli CJ, Houchins JA, et al. The impact of doubling dairy or plant-based foods on consumption of nutrients of concern and proper bone health for adolescent females. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20:824–31.

- Weaver CM. How sound is the science behind the dietary recommendations for dairy? Am J Clin Nutr. 2014; 99(5 Suppl):1217S–22S.

- US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. 9th Edition. December 2020.

- European Commission. Food-based dietary guidelines in Europe: Summary of FBDG recommendations for milk and dairy products for the EU, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland and the UK. 2021.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Promoting a healthy diet for the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region: user-friendly guide. 2012.

- ANSES. Table Ciqual des aliments; Directive européenne (90/496/CEE). 2008.

- Martin A. The “apports nutritionnels conseillés (ANC)” for the French population. Reprod Nutr Dev. 2001;41:119–28.

- Cifelli CJ, Agarwal S, Fulgoni VL. Association of yogurt consumption with nutrient intakes, nutrient adequacy, and diet quality in American children and adults. Nutrients. 2020;12:3435.

- Vatanparast H, Islam N, Prakash Patil R, et al. Consumption of yogurt in Canada and its contribution to nutrient intake and diet quality among Canadians. Nutrients. 2019;11:1203.

- Hess JM, Fulgoni VL, Radlowski EC. Modeling the impact of adding a serving of dairy foods to the healthy Mediterraneanstyle eating pattern recommended by the 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. J Am Coll Nutr. 2019;38:59–67.

- Hobbs DA, Givens DI, Lovegrove JA. Yogurt consumption is associated with higher nutrient intake, diet quality and favourable metabolic profile in children: a cross-sectional analysis using data from years 1–4 of the National diet and Nutrition Survey, UK. Eur J Nutr. 2019;58:409–22.

- Melini F, Melini V, Luziatelli F, et al. Health-promoting components in fermented foods: an up-to-date systematic review. Nutrients. 2019;11:1189.

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. 2015.

- World Health Organization. Healthy Diet Factsheet 2020.

- National Dairy Council (Nutrition Impact, LLC analysis. Ages 2+ years, NHANES 2007-2008, 2009-2010). NHANES 2007-2010 food and beverage sources of added sugars in the diets of children (2-18 years) and adults (19+ years).

- Azaïs-Braesco V, Sluik D, Maillot M, et al. A review of total and added sugar intakes and dietary sources in Europe. Nutr J. 2017;16:6.

Lauren Twigge is a Dallas based registered and licensed Dietitian with a Master’s degree in Clinical Nutrition and a bachelor’s degree in Animal Science. Along with running her own nutrition company and working with private clients, Lauren works as social media dietitian, recipe developer, blogger, and brand ambassador. Lauren was born and raised in a family of farmers located in central California and is an outspoken supporter of the agricultural industry. Growing up on a dairy and being raised around farming her whole life has given Lauren a unique perspective on where our food comes from and her passion is to work at the crux of agriculture and human nutrition to fight misinformation and give consumers back their food confidence. Lauren is on Instagram @nutrition.at.its.roots and educates on a variety of health topics including the truth about the agricultural industry, education on where our food comes, and discussing the role that various agricultural products, like milk, can play in a healthy diet!

Lauren Twigge is a Dallas based registered and licensed Dietitian with a Master’s degree in Clinical Nutrition and a bachelor’s degree in Animal Science. Along with running her own nutrition company and working with private clients, Lauren works as social media dietitian, recipe developer, blogger, and brand ambassador. Lauren was born and raised in a family of farmers located in central California and is an outspoken supporter of the agricultural industry. Growing up on a dairy and being raised around farming her whole life has given Lauren a unique perspective on where our food comes from and her passion is to work at the crux of agriculture and human nutrition to fight misinformation and give consumers back their food confidence. Lauren is on Instagram @nutrition.at.its.roots and educates on a variety of health topics including the truth about the agricultural industry, education on where our food comes, and discussing the role that various agricultural products, like milk, can play in a healthy diet!