Shrinking the share of animal protein in our diet has become a focus for protecting both human and planetary health. But, while reducing animal protein is set to ease pressures on the environment, it could also come at a cost, latest research reveals (1).

If not carefully designed, our low animal protein diet could spell bad news for the wealth of the world’s fauna and flora which could fall victim to the changing agricultural practices.

The findings, based on diet modelling, have led researchers to call for further research into the best balance of animal-sourced protein in our shift towards more sustainable, plant-based diets. The modern diet should take account of all influences on sustainable eating and may require radical changes in our agriculture, the researchers say.

Modelling sustainable diets for human and planetary health

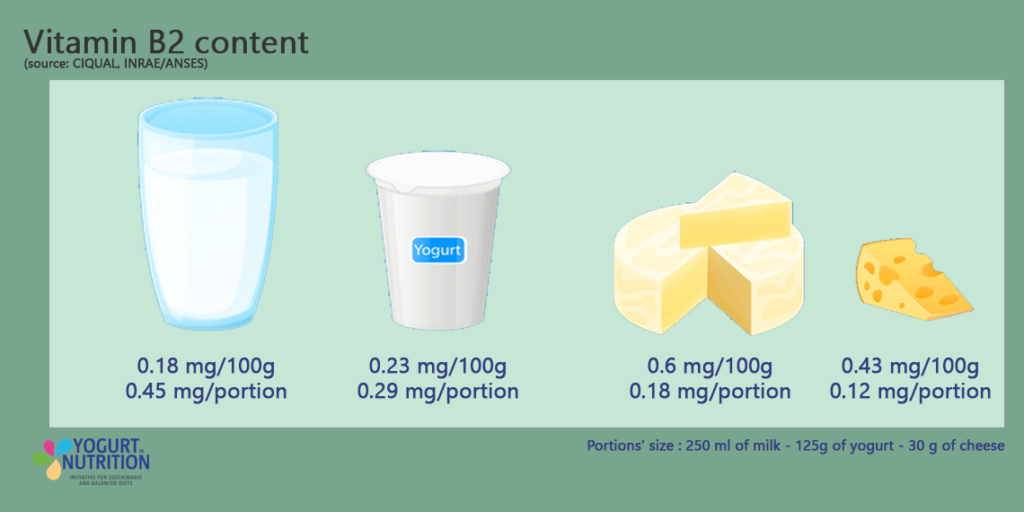

Environmental pressures created by the global food system are driven mainly by the high proportion of animal products in our diet (2). Reducing the share of animal-based foods we eat could therefore bring major benefits to the environment (3) and is a key target of food policies to increase sustainability (4,5). But because animal products are such an important source of protein and micronutrients, cutting down on them also risks making the diet less affordable or acceptable (6,7). Optimized diets may have difficulty to meet the requirement for certain nutrients (calcium, vit. B6 or B12, vit D, iodin), some of them being specific animal-sourced micro-nutrients.

Adding to this dilemma, a team of French scientists has shone a spotlight on the pros and cons for the environment of reducing animal protein in our diet (1).

They previously explored the minimum share of animal protein that met all food nutrient recommendation (8). For this new publication, using a national database of French adults’ diets, they developed five model low-animal-protein diets for different groups of adults based on gender and age. The observed diet is not fulfilling all nutrient recommendations, but these low-animal-protein diets contained the least animal protein needed to fulfil nutritional needs – around 50% of dietary protein – while minimising changes in the quantity and affordability of food consumed.

A low animal protein diet contains more fruits and vegetables (+103%), pulses, potatoes and unrefined grain products (+142%), more eggs (+96%), more dairy products but with variations within this category, with more milk (+222%), the same quantity of yogurt and less cheese (-97%) and of course, less meat –66%).

Tracking ecological impacts from field to fork

The researchers then used a lifecycle assessment to compare the environmental impacts of model low-animal-protein diets with those of typical French observed diets, where around 70% of protein is from animal sources. This method tracked various ecological effects from ‘field-to-fork’, including farming, processing, packaging, transport, retail, consumer use, and waste disposal. Here’s what they found…

Cutting down on animal protein has positive effects on the environment

Results suggested that reducing the share of animal protein from 70% to 50% of total protein intake could significantly ease several key environmental pressures. Differences between typical and low-animal-protein diets were similar for each of the five groups of adults studied:

- Greenhouse gas emissions (GHGE): The levels of GHGEs fell by 30% in the modelled low-animal-protein diets, potentially helping to curb climate change.

- Acidification: Emissions of acidifying gases, which can damage soil and water quality, fell by 40%.

- Land occupation: The area of land needed for food production shrank by 35% with low-animal-protein diets.

- Energy demand: The energy consumed throughout the life cycle of food products dropped by 24%.

- Marine eutrophication: Nutrient runoff into marine environments, due to the emission of nitrogen compounds, fell by 13%.

Reducing animal protein can also have harmful environmental impacts

On the down-side, the researchers uncovered some concerning trade-offs that could occur with low-animal-protein diets, particularly in water use and biodiversity:

- Freshwater eutrophication: Nutrient runoff into freshwater environments, due to the emission of nitrogen or phosphorus compounds, rose by 36% with low-animal-protein diets.

- Water use: There was a 41% rise in the amount of water needed for food production associated with low-animal-protein diets.

- Biodiversity loss: The estimated loss of species associated with changes in land use due to food production soared by 66% with low-animal-protein diets.

How can we balance these mixed environmental impacts?

The results of this modelling study suggest that cutting the share of animal protein we eat to 50% is compatible with nutritional needs, affordability and consumption constraints, but could have mixed effects on the environment. Therefore, any shift toward low-animal-protein diets should be carefully managed to balance these environmental trade-offs.

When designing sustainable diets, while covering all nutrient requirements of a population (taking into account age, gender and physical status specificities) it is important to consider all aspects of sustainability, the researchers say. In the modelling, they found that environmental benefits were driven by decreases in red meat consumption while introducing the concern on its impact on biodiversity. Increased consumption of fresh fruits, vegetables and fatty fish explained most environmental challenges related to water use.

The researchers propose that shifting the shares of plant and animal products in diets may require transforming agricultural practices and food systems to address concerns about climate change, biodiversity preservation and water consumption.

“While shifting toward a more plant-based diet is promoted, especially in Western countries, the optimal share of animal protein compatible with a sustainable diet has yet to be determined.”