Phosphorus is an essential nutrient for many functions and body parts such as bone and teeth. It is present in dairy, let’s focus on it.

What is phosphorus?

Phosphorus is a mineral found in many components of the body. 85% is found in bones and teeth, 15% in blood and soft tissues and it makes up to 1-1,4% of the fat free mass of the body.

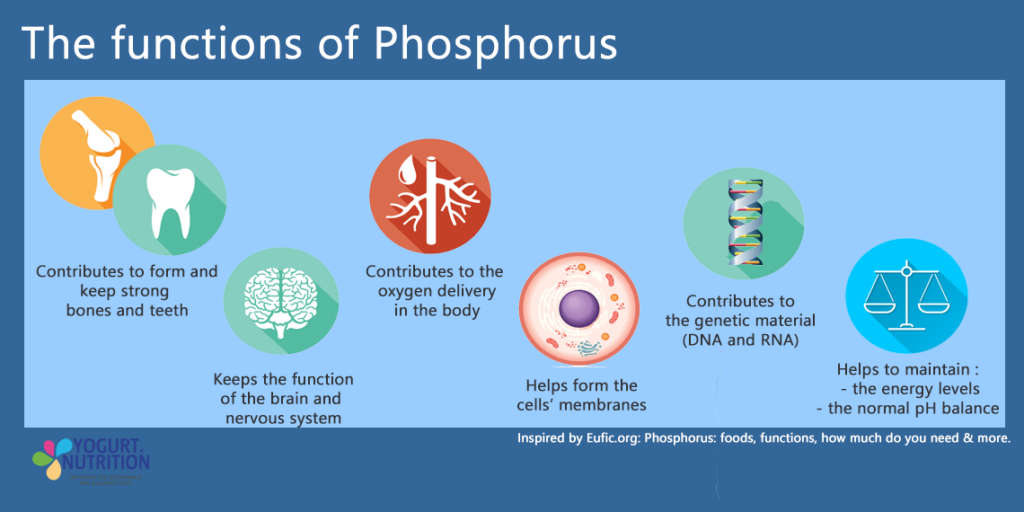

Phosphorus plays a role in a multitude of processes:

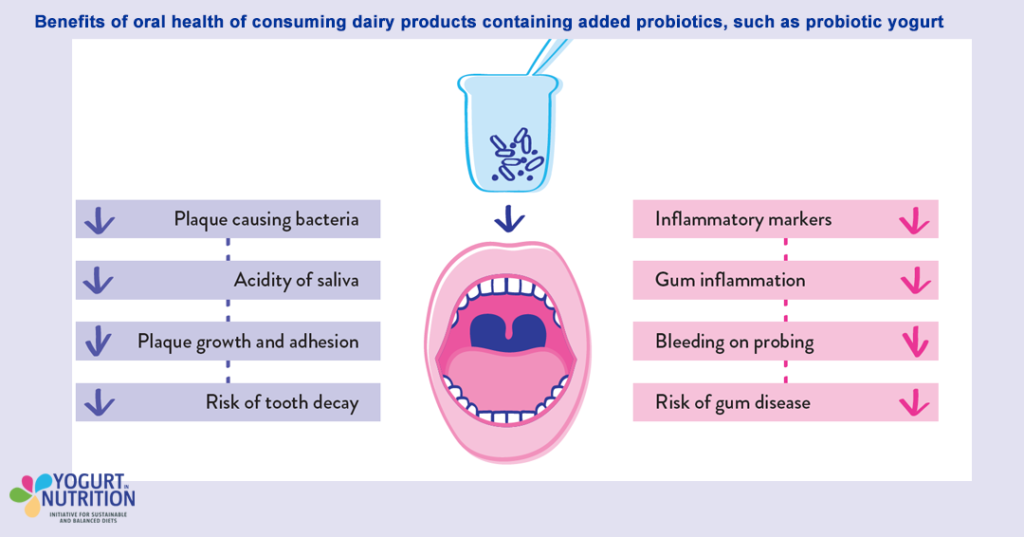

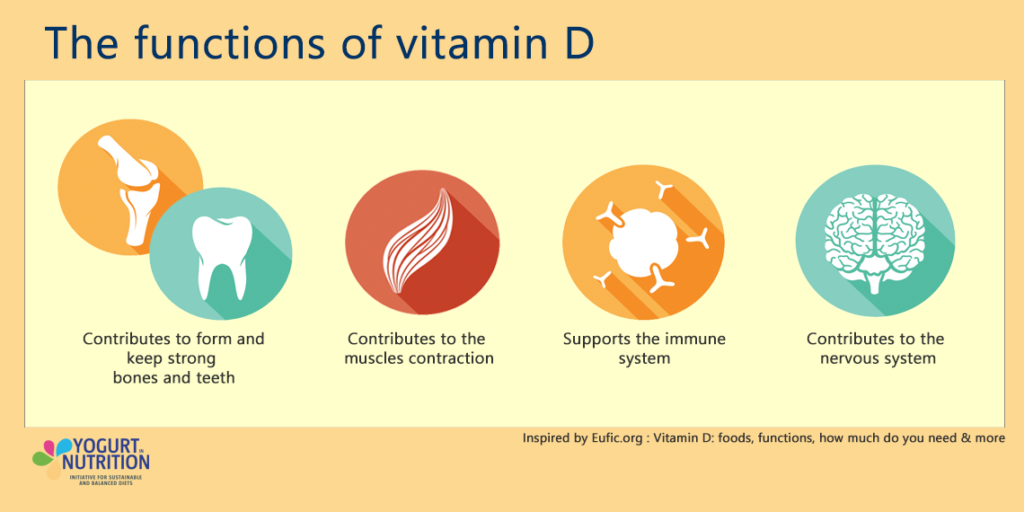

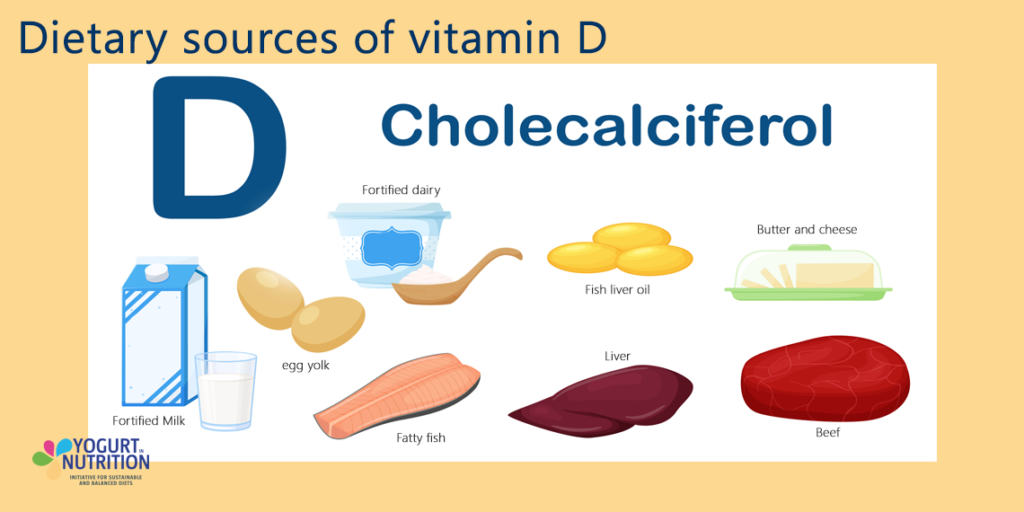

- Bones and teeth structure. Along with calcium it forms hydroxyapatite which is the main structural components of bones and enamel. They are regulated by vitamin D which means these 3 nutrients are interrelated for bone health.

- Cell membranes: it is present in phospholipids which make up the majority of the cell membranes and it contributes to the to the normal functioning of cell membranes

- Part of the body’s key energy source: it is part of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) which is the source of energy of the body in metabolic processes and it supports normal energy metabolism.

- DNA and RNA: it is present in the backbone of the molecule and has a role in gene transcription and activation of enzymes

- Nervous system: it protects the cells and provides energy.

- pH balance: it acts as a buffer in extracellular fluids.

- Oxygen delivery to cells: it binds to haemoglobin to regulate oxygen delivery.

- Phosphorylation of sugars and proteins: it is the first step to convert them to usable energy by the body.

Deficiency in phosphorus can lead to symptoms of anaemia, loss of appetite, muscle weakness, confusion, increased infection risk and of course bone diseases (bone pain, rickets, osteomalacia, osteoporosis).

According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in the USA, most Americans consume more than the recommended amounts therefore deficiency is rare and most likely not a result of low dietary intakes.

Dietary recommendations

The recommended daily intake of phosphorus for adults is 700mg. For teenagers, a higher intake (1250mg) is recommended to accommodate rapid growth and to ensure healthy bones.

In a healthy and balanced diet, it is unlikely to consume too much phosphorus to the point of having negative health effects as the safe upper limit is 3000 mg per day.

Phosphorus can be found in many different types of food especially those high in protein such as dairy, meat, fish, grains and legumes.

In some food products, the bioavailability of phosphorus remains poor. For example, in unleavened bread and seeds it is found in its storage form of phytic acid. The body lacks the phytase enzyme to break it down and absorb the phosphorus.

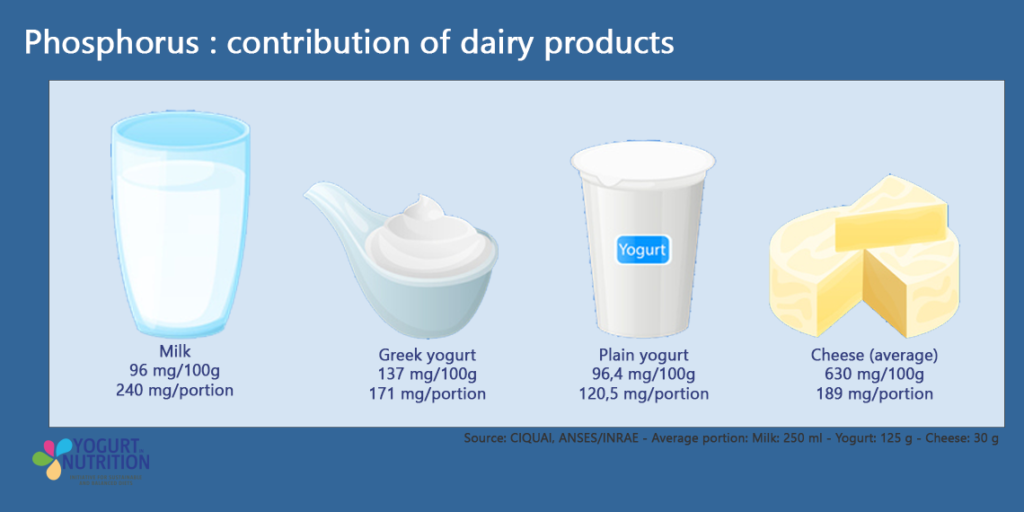

Phosphorus in dairy

Dairy represents about 20% of total phosphorus consumption in the USA. Dairy also contains calcium and vitamin D which are the other micronutrients essential for bone health.

Keeping a good calcium/phosphorus ratio is important. If phosphorus is consumed in high amounts and calcium in low amounts, the high amount of phosphorus will prevent some of the calcium to be absorbed causing low levels of calcium and issues for bone health. The same is true the other way around.

Dairy products are a good way to get some bioavailable phosphorus as well as other micronutrients involved in bone and overall health.

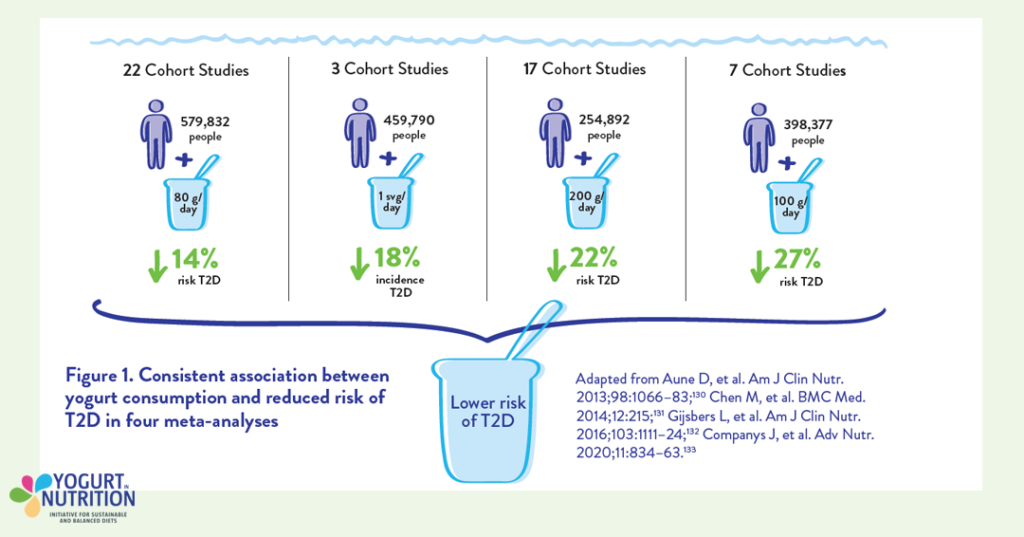

Studies show that people who consume yogurt have stronger bones and better mobility in older age. Yogurt consumption of is also associated with higher bone mineral density in children

It is recommended to consume 2-3 portions of dairy per day.