Gut health and fermented foods: what’s new?

At YINI, we discovered many usefull and learning ressources developped by the website Gut Microbiota For Health (GMFH) and wanted to share some of them with you.

Gut Microbiota for Health (GMFH) has been created by the Gut Microbiota and Health Section of the European Society for Neurogastroenterology & Motility (ESNM), member of United European Gastroenterology. The goal of GFMH is to raise awareness and interest on the gut’s bacterial community and its importance for our health and quality of life both among the scientific and medical community and society in general.

Fermented foods

We invite you to visit the GMFH website and discover the well-made infographics and specifically this recent infographic about the benefits of fermented foods.

What do yogurt, beer, and sourdough bread, have in common? They are all foods that depend on the activity of microorganisms for their taste, texture, and digestibility. In other words, they are fermented foods. Through 2 infographics, GMFH experts detail the benefits and limits of the fermented foods on gut and microbiota.

For the last Gut Microbiota World Health Summit, held in March 2019 in Miami, top gut health researchers from around the globe convened to present their research, furthering our knowledge base in this area. Lori Shemek, PhD, was invited to attend the Summit and we have the pleasure to share her report and key messages of the Summit.

The past ten years we have seen remarkable advancement in our understanding of the gut microbiota and its impact upon human health.

The impact of our gut microbiome on our overall health, brain health, weight and much more, cannot be overstated. The human body, it is becoming more apparent, cannot live without gut microbes. We depend upon these many diverse bacterial species for our optimal health.

Because the gut microbiota function is so important and unique, it has now been described it as a ‘supra organ’ an organ equally and powerfully as important as any other organ in the body. All organs work together to keep the human machinery alive and well and the gut is a powerful member.

Why is the health of the gut so important? Within our gut we have roughly 40 trillion bacterial cells in your body and only 30 trillion human cells. That means you are more bacteria than human. Additionally, you have up to 1,000 bacterial species where each plays a different role that are crucial for digestion of food, immune system, heart health, weight, brain health and other bodily processes.

“This microbiome or ‘communities’ have a powerful effect upon one’s quality of life.”

In attending this summit, there were a few pieces of research presented that had an effect upon my views: first of all, the probiotic effect on gut health.

One of the many key takeaways is that we are moving from the current ‘one size fits all’ microbiome treatment approach, such as simply taking a general probiotic supplement to benefit the gut, and more towards an integrated personalized microbiome treatment approach.

Probiotics are typically bacteria or other living organisms, like yeasts. Probiotics are usually found in foods or dietary supplements such as a pill or powder, or in fermented and cultured foods, such as yogurt.

I’ve routinely recommended a probiotic supplement or fermented food to enhance gut health and particularly after a round of antiobiotics. Antibiotics destroy all gut flora, both beneficial and harmful. However, research presented during a session of the event by Purna Kashyap, MBBS and Pinaki Panigrahi, MD, PhD, prompted the inherent question ‘should we routinely recommend a probiotic after antibiotic treatment?’ The answer is probably not until more research is published.

The outcomes with probiotic use are unique to each individual in terms of the colonization of probiotics. Colonization with probiotics varies between individuals; some people are “resistant” and some are “permissive” to a particular probiotic that compels a more individualized approach. This variation and the lack of data means that more studies are needed.

Additionally and surprisingly, Eran Elinav, MD, PhD, presented some results showing that after the use of antibiotics, probiotic supplementation can delay the reconstitution of beneficial gut microbiome and may promote long-term suppression of the indigenous microbiome. It is important to stress that it is probiotic supplement use only.

Probiotics in food however, can be safe and useful. Cultured and fermented food, a natural food-based source of probiotics, is an excellent choice. For example, yogurt has a combination of multiple probiotic species that may improve IBS symptoms as well as optimizing gut health.

However, depending upon genetics, gut health or one’s health in general, probiotic supplementation could be detrimental and it now appears it is not a blanket recommendation for everyone.

“The bottom line is probiotics work differently in different people. We need more evidence with better-designed studies”.

Lori Shemek, PhD @lorishemek

Thank you to Lori Shemek, PhD for her work and feedback.

Childhood is a decisive period for laying the foundations of positive and life-long healthy eating habits. A report from a group of experts, Nurturing Children’s healthy eating, shows the key role of families to build good eating habits in children. Every month, we will bring you a synthetic post, highlighting some of the key messages taken from this report, in order to help families nurture healthier eating habits.

Around the World, millions of children learn by imitating their parents and family members, who become role models. Families play a crucial role in giving healthy behaviours to their children including eating habits, in order to raise them with strong learnings for a healthy future.

“Future global health depends on the health of today’s children. Those children who establish healthy eating and activity behaviours early in life are well-equipped to maintain their good health far into adult life.”

Families shape eating behaviours of children from conception to adolescence: they decide what to eat, but also how, with who and when to eat.

Families and the home environment could be fantastic sources of positive influences for children by showing them healthy habits and determining their food choices. A strong body of evidences showed that weight, BMI and eating behaviors are greatly influenced by the parents and the family.

It is important to communicate to families that the challenge of instilling healthy eating habits in children is not only about what to eat but also about how, when and how much to eat. Families have a pivotal role in promoting and supporting healthy eating!

A family-centered approach is a key opportunity to improve not only eating habits but also the pleasure to eat healthy foods.

Eating is a social experience, parents and family members can transmit values to children to help them develop and keep these healthy eating habits in the future. Families can also convey the idea that healthy foods is not only good for health but also good to eat.

Family can contribute to build a positive image of healthy foods by associating healthy foods with tasty and enjoyable foods and moments.

However, even knowing how to act, experts pinpoint the fact of a difficult context. The main difficulty is to find a balance between work and family, leisure times, children more and more engrossed by screens… modern life has changed the organisation of families and their time management. Families are busy and spend less time preparing meals and eating together. However, experts insist on the necessity to combine education to healthy foods with busy schedules.

The group of experts identified three key pillars to support families when nurturing healthy eating :

Today’s family education determines future individual and global health, this is why families have such a great role to play!

A happy gut means a healthy mind and body. Unlocking all the secrets held in our guts and understanding what influences them could help us combat a raft of health conditions. That’s why the gut microbiota – the trillions of bacteria that inhabit our gut and play a vital role in keeping us healthy – are one of the hottest topics in scientific research today.

The types of bacteria that make up our gut microbiota are determined largely by what we eat and drink. Fermented foods, such as yogurt, bread and kefir, may help to ensure a healthy balance of bacteria in the gut, and research is investigating whether such foods can promote good health and prevent disease.

In this review, the authors look at the role of fermented foods and drinks on the gut microbiota and consider future directions and collaborations for research.

Our guts control and deal with every aspect of our health, say the authors. How we digest our food is linked with our mood, behaviour, energy, weight, hormone balance, immunity, and overall wellness.

Closely linked to the workings of our gut is the gut microbiota, the community of bacteria found throughout our digestive system but especially in the bowel. A diverse and healthy gut microbiota plays fundamental role in maintaining our health and wellbeing, say the authors.

The composition of the microbiota differs from one person to another, but most people have several types of bacteria in common. The healthy bacteria produce enzymes that help to digest food, they make vitamins and they help to maintain overall gut health. A large part of the body’s immune system is found in the tonsils and gut, so gut health is closely linked to the health of the immune system.

Evidence suggests that disturbance of the healthy gut microbiota may be involved in inflammatory diseases, which are linked to obesity, depression and other mental health issues. Changes in the microbiota may also be associated with diabetes and heart disease.

‘…one cannot be considered to be in good health without a well-balanced microbiota composition in the gut, our “forgotten organ”….’ – Bell et al, 2018.

Fermented foods and drinks have become increasingly popular as people learn more of their possible health benefits.

Fermentation helps to preserve foods, may improve taste and texture and, by ‘pre-digesting’ food components, makes foods easier to digest and absorb.

Fermented foods are made using microbes, but not all fermented food products contain live microbes because they may be inactivated or removed during processing.

Some people mistakenly think that fermented foods and probiotics are the same thing. Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host. Fermented foods are not necessarily probiotics, although they may contain them. If so, they’re useful because they help provide a spectrum of bacteria, such as probiotics, that may provide health benefits through encouraging a vigorous microbiota community.

When fermented foods contain probiotics, they may provide extra nutritional and health benefits. In fact, the health benefits of fermented foods seem to come from the probiotics they may contain.

‘The limitations and inconsistencies in the current body of evidence mean that, presently, no definitive conclusions can be drawn on the potential health benefits of fermented products.’ – Bell et al, 2018.

Research on the potential health benefits of probiotics is still emerging but so far it is mostly being carried out by the food industry. We need independent scientific evidence to support the use of probiotics for specific health conditions, say the authors. Probiotics help to re-balance the microbiota by introducing beneficial microbes and destroying harmful ones.

Studies suggest that probiotics may help with diarrhoea and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. It is likely that the effects of probiotics may vary in different people, say the authors.

If you’ve ever had to take antibiotics, the chances are you’ve experienced the down-side as well as the benefits. Diarrhoea is a well-recognised problem of antibiotic treatment, and is thought to arise because of an upset in the bacteria that normally live in our intestine – the gut microbiota.

In the search for a solution to antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD), research is focusing on clarifying the role of probiotics in helping to restore the natural balance in the gut microbiota and so prevent the unwelcome effect. Probiotics are ‘friendly’ microbes – live microorganisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.

Yogurt naturally contains two strains of microbes that are used in the fermentation of milk to yogurt (Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus). But yogurt also makes a perfect vehicle for adding further potentially helpful microbes, or probiotics.

Some probiotic strains may help to prevent AAD in adults and children, but few studies have looked specifically at the potential benefits in hospitalised patients. People who are in hospital are particularly susceptible to AAD because they may be debilitated by more than one illness.

The authors of this study recruited 314 people, mostly elderly, who were prescribed antibiotics (amoxicillin-clavulanate or levofloxacin) in a Spanish hospital. The study looked at the effects on the occurrence of AAD of standard yogurt compared with yogurt supplemented with additional probiotics.

The participants were randomly assigned to receive a cup of yogurt drink supplemented with three strains of probiotic, or standard yogurt that did not contain the additional strains. A third group didn’t receive any yogurt and so formed a control.

Each participant started the ‘treatment’ within 48 hours of beginning the course of antibiotic and continued until 5 days after stopping the antibiotic. The participants were followed up for a month to see if they suffered any episodes of diarrhoea.

Results suggested that neither the probiotic yogurt nor standard yogurt appeared to prevent AAD.

During the one-month follow-up, 23% of participants in the probiotic-supplemented yogurt group suffered diarrhoea compared with 17.6% in the standard yogurt group – a difference that was not statistically significant. The severity of diarrhoea was also similar in the two groups. And there wasn’t much difference between rates of diarrhoea in the yogurt groups and the control group.

‘…our study does not support a role of the combined probiotic strains L. acidophilus LA-5, B. lactis BB-12 and L. casei LC-01 in the prevention of AAD in hospitalized (mostly elder) patients.’ – Velasco et al, 2018.

The strains of supplemented probiotic used in this study were Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5, Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BB-12 and Lactobacillus casei subsp. casei LC-01).

These probiotic strains were found to be sensitive to the antibiotics taken by the participants in this study, and this might have contributed to the apparent lack of benefit. It is possible that not enough of the probiotic survived in the gut to have an effect on AAD, say the authors.

Previous studies have suggested that other probiotic strains do have positive effects when it comes to AAD prevention. It would be well worth conducting more studies of specific probiotic strains in AAD prevention in different clinical settings, say the authors.

Evidence also suggests that probiotics may be less effective at preventing AAD in the elderly. More studies on probiotics and AAD are needed in older hospitalised patients before any firm conclusions can be drawn, say the authors.

‘Up to now, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Saccharomyces boulardii are the only species that have demonstrated a protective effect on AAD in children and adult patients.’ – Velasco et al, 2018.

If you’re planning to help save the planet by cutting down on animal products in favour of more plant-based dishes, think again. The chances are you could be contributing to even more damage to the environment, according to this report.

That’s because animal-based foods such as dairy products contain nutrients that aren’t so easy to get from plant-based foods. The problem comes when you compensate for the lost nutrients in order to keep up a healthy nutritious diet, say the authors.

In their research, they calculated the environmental impact of the food we eat and what happens if we make changes to our diet.

Results revealed that the popular move to switch to a more plant-based diet doesn’t necessarily reduce our environmental footprint at all – and it can even make it bigger, say the authors.

But there are some changes we can make to our daily diet that could make a difference to protecting the world we live in.

About a quarter of our carbon emissions come from our food. Many animal products – especially beef – generate higher carbon emissions than plant-based foods. Beef also stands out in our diet as taking up by far the largest land use per kg of food product, say the authors.

But other foods can also place a surprisingly heavy burden on the environment, often through transport and distribution. Hence a banana imported from South America has a bigger footprint than a locally-grown apple, for example.

‘Following a healthy and sustainable diet is not as easy as it might seem.’ – van Est L et al, 2017.

To unravel the puzzle, the authors assessed the nutritional content and environmental impact from farm to plate of each of 208 products eaten regularly in the Netherlands where the research was based.

With the average Dutch diet as a starting point, the authors used a mathematical model to calculate how replacing certain parts of the diet would affect its carbon footprint. For every 20 g change in a food group, the model worked out the carbon footprint and land use of the alternative diet, always making sure the new diet provided enough of all the nutrients we need to comply with dietary guidelines.

Not surprisingly, the results showed that the more beef we eat, the higher the environmental impact of our diet. On the other hand, changing the amount of dairy products we eat has a negligible impact on the environment.

That’s because dairy is such a nutrient-rich food that if you leave it out of your diet, you’ll have to eat loads more fruit and vegetables – spinach to provide the calcium, for example – to make up for the nutrients you would have got from dairy products and so reach your recommended daily intakes. When you add up the environmental effects of the replacements, you get roughly the same environmental effect as if you’d stuck with your dairy products, the authors found.

‘The sustainable principle to eat less animal-based products and more plant-based products does not automatically result in a more environmentally-friendly diet.’ – van Est L et al, 2017.

The model revealed that two plant-based food groups that do have a positive effect on the environment are bread and nuts and seeds. These foods are relatively rich in nutrients and the environmental impact of the diet falls as we eat more of them.

Next the authors applied their model to 10 daily menus recommended for meeting the Dutch national dietary guidelines and compared these menus with the average Dutch diet.

If a more sustainable diet involves eating less meat and more plant-based foods then these healthy recommended menus could be expected to have a lower environmental impact than a typical Dutch menu of meat, cheese and other diary products. But half of the recommended menus – even the ‘no meat today’ menu – had a higher environmental impact than the average Dutch diet. The ‘I love Holland’ daily menu – of meat, dairy products, fruit and vegetables from Dutch farms – had the lowest environmental impact of all.

So the authors conclude that it’s hard to come up with a more sustainable diet that involves eating less animal-based and more plant-based products than most people do now in Western Europe. That’s because, while an exotic fruit needs to be transported, locally grown produce has a much shorter, and environmentally cheaper, trip before it lands on our plate.

“If you eat lots of exotic fruit and vegetables, it is difficult to achieve a sustainable footprint.” – van Est L et al, 2017.

So, what to do? For many of us in Western society, the answer is simple. People who eat too much can take a big step towards saving the planet by cutting down to sensible levels. For example, the authors calculated that a man who eats too much can almost halve his carbon emissions by switching to the recommended calorie intake for men of roughly 2,600 kcals per day. For women, the recommended intake is about 1900 kcals per day.

The authors warn that the science behind what makes a sustainable and healthy diet has a long way to go and further research is needed to confirm their conclusions.

In the meantime, don’t forget that your diet is just one cog in the wheel when it comes to sustainability and that the way you lead your life can have a bigger impact on the environment than your food. For example, any good you might have done the environment by following a sustainable diet for a year will be undone if you then take a long-haul flight to go on holiday.

At YINI, we discovered many usefull and learning ressources developped by the website Gut Microbiota For Health (GMFH) and wanted to share some of them with you.

Gut Microbiota for Health (GMFH) has been created by the Gut Microbiota and Health Section of the European Society for Neurogastroenterology & Motility (ESNM), member of United European Gastroenterology. The goal of GFMH is to raise awareness and interest on the gut’s bacterial community and its importance for our health and quality of life both among the scientific and medical community and society in general.

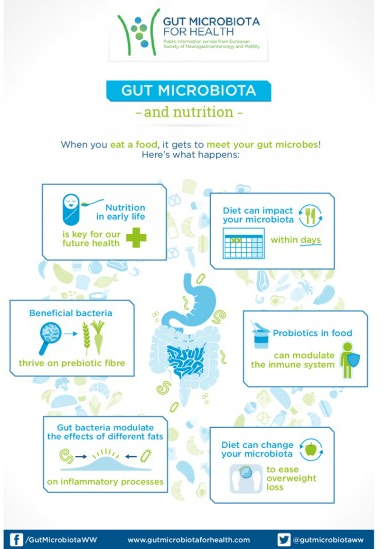

We invite you to visit the GMFH website and discover the well-made infographics, like this one detailling the role of nutrition about our gut microbiota:

“The power of food to impact your health is not a new idea, but it is only with emerging research on the human gut microbiota that scientists are beginning to understand exactly how this happens. Whether you eat a strawberry or a hamburger, the food components enter your digestive system and encounter the intestinal microbes. Through a series of complex events, the microbes living in your gut influence how your body processes the food. And in turn, the food can change the microbial community living inside you. The products of these diet-microbiota interactions can profoundly change your health. ‘You are what you eat’ has never been so true!.”

Switching to a sustainable food system may require us to face challenging choices as a society and these may need vigorously defending against powerful lobbies, say the authors of this review.

In the meantime, experts around the world are becoming increasingly concerned about the lack of sustainability of our food system. But the experts disagree over how bad the crisis is and how best to go about fixing the problem. Even the concept of sustainability means different things to different people, with no clear consensus on which policy-makers can act, the review has revealed.

Feeding the world isn’t just a case of producing more food, say the authors. Rather, we need to consider nutrition and diet quality, and environmental and economic impacts of producing and distributing food. The food system should also be set up to tackle malnutrition – eating too little, too much, or inadequate nutrients.

Hence the aim of a sustainable food system initiate is to make food available, affordable, accessible and acceptable to our varied populations.

Many proposals have been put forward to help solve the food system crisis. The authors reviewed over 70 documents on the food system, including academic articles, books, and government reports. They analysed the ‘stories’ around food systems described by the experts – what is the problem, what are the threats and the solutions, and where do the priorities lie?

In the light of their review, the authors propose a framework built around outcomes, activities and trade-offs in a bid to support our switch to a more sustainable food system.

Their analysis showed wide agreement that the main objective of a food system is to deliver food and nutrition security – reliable access to enough nutritious food. Through this focus, the food system can also contribute towards improving people’s health.

The environmental and socioeconomic impacts of our food system need to align with population growth and the land’s capacity. Improvements here will depend partly on making farming a more attractive lifestyle for young people, and efficient use of resources, say the authors.

But further pressure will come from climate change , and our future food system must become resilient to a fall in productivity in several key crops around the world, as well as local droughts and floods, in turn leading to the risk of price rises and social unrest.

As well as food security, we need to consider diet quality. Recent changes in food systems have led many of us to eat unhealthy diets, with more and more of us becoming overweight or obese and suffering the associated diseases. Improving diet is a high priority when it comes to plans for a sustainable food system, say the authors.

But the foods we eat must be acceptable within our culture, and food systems that are culturally acceptable aren’t necessarily the most healthy or environmentally friendly. So shifting from our current systems to more sustainable diets may face opposition, the authors warn.

‘Changing diets or food habits to achieve sustainability is more easily said than done, given that culture is not something that can be changed overnight.’ – Bene C et al, 2019.

A shift to a sustainable food system would also need to address the challenges posed by food production, processing, transport and retail, all of which place a strain on the environment through their use of fossil fuels and electricity. But some communities still don’t acknowledge this need, and solutions have yet to be found, say the authors.

‘… some powerful lobbies will have to be aggressively challenged.’ – Bene C et al, 2019.

Our shift to sustainability will inevitably demand trade-offs between food security, nutrition, health, income, environmental impact, and culture within our food system, the authors point out.

For example, setting up cold storage facilities for products may reduce the amount of food wasted but comes at the cost of a higher environmental impact – a cost that’s often not factored in during proposals for future food systems.

The chances are that we won’t be able to come up with a win-win situation in which a sustainable food system initiative benefits all these different dimensions. As a society, we’ll have some tough decisions to make about where the priorities lie.

The authors conclude that research should focus on helping us make these difficult decisions by giving us a better understanding of the trade-offs involved in food system sustainability.