This Digest is all about #Snack #Yogurt & #Definitions #Recommendations

Snacking thoughts

Do you like to snack? If so you aren’t alone. Money spent on snacking is increasing year on year; the global annual market is currently worth $374 billion (1), and research points to snacking making a significant contribution to average daily energy intakes (2).

Making healthier food choices and reducing calorie intake in our food-filled environment can be challenging. It requires planning, nutrition knowledge, portion control, label reading skills and calorie awareness. Strategies that simplify the process and provide more structure have been shown to be helpful. For example, using goal setting techniques with a specific plan of how to achieve the goal, creating meal and snack plans, advising on portion controlled foods, and devising shopping lists (3).

Snacking is often considered undesirable, but it all depends on what you choose to eat! Reach for a low sugar cereal bar and you’ll be contributing to your fibre intake, popcorn offers you whole grains and a pot of yogurt will bring a healthy serving of calcium and protein. Such foods may be particularly important for children who may have inadequate fibre or calcium intakes.

What does the evidence say? Does it depend on what we choose to snack on? And how can we tell if a snack is healthy or not?

References:

1. The Nielsen Company, SNACK ATTACK : What consumer are reaching for around the world, September 2014

2. Janette C Brand-Miller, Susanna HA Holt, Dorota B Pawlak, and Joanna McMillan. Glycemic index and obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76(suppl):281S–5S 3.Foster GD, Makris AP, Bailer BA. Behavioural treatment of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005; 82 (suppl): 230S-5S.

3. Foster GD, Makris AP, Bailer BA. Behavioural treatment of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005; 82 (suppl): 230S-5S.

To snack or not to snack – nutrient intakes and energy for activity

How snacking influences nutrient intakes

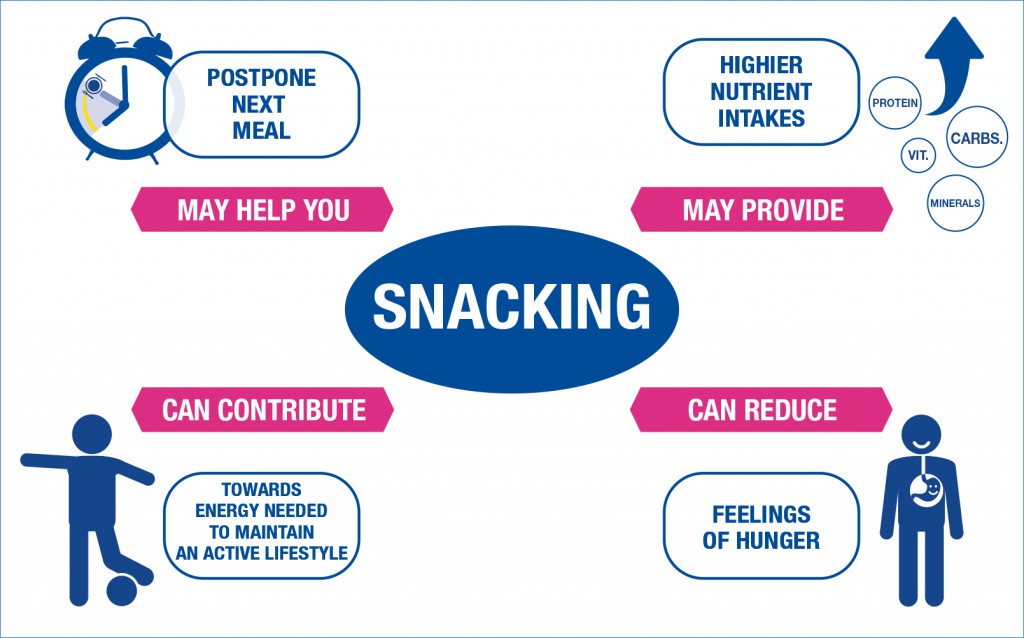

It is important to look at the overall contribution of snacks and whether they provide a nutrient dense addition to the diet, or whether they are a source of what’s often called “empty calories”.

Some studies show that eating snacks has been linked to greater intakes of vitamins and minerals (4-8). In a study of UK children aged 11–12, Adams et al. (5) found no evidence to suggest the nutrient composition of snacks was any more or less healthy than that of foods eaten during meals. Perhaps surprisingly, snacking may also not lead to a higher intake of sodium (salt), as the sodium contribution from meals (from foods such as bread, cheese and cured meats) has been associated with higher sodium intakes (9).

More research is needed, but based on current evidence, snacking and increased eating frequency may not be necessarily detrimental to diet quality and may be associated with a higher nutrient intake. However, careful snack choice by individuals remains important to avoid the risk of excessive intakes of energy, fat, sugar or salt (2).

Snacking and energy for activity

Snacking may help to provide the energy needed to maintain an active lifestyle and increase the motivation to be physically active – for example, by avoiding the gastric discomfort and lethargy that can be experienced after consuming large meals (10).

References:

4. Haveman-Nies A, de Groot LP, van Staveren WA. Snack patterns of older Europeans. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998 Nov;98(11):1297-302.

5. Jean Adams, Marilyn O’Keeffe and Ashley Adamson. Change in snacking habits and obesity over 20 years in children aged 11 to 12 years. Project NO9 019 (Jan-Sept 2005)

6. Stroehla BC, Malcoe LH, Velie EM. Dietary sources of nutrients among rural Native American and white children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005 Dec;105(12):1908-16.

7. Jean M. Kerver, Eun Ju Yang, Saori Obayashi, Leonard Bianchi, Won O. Song. Meal and Snack Patterns Are Associated with Dietary Intake of Energy and Nutrientsin US Adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:46-53.

8. Sameera A. Talegawkar, Elizabeth J. Johnson, Teresa Carithers, Herman A. Taylor Jr., Margaret L. Bogle, and Katherine L. Tucker3. Total a-Tocopherol Intakes Are Associated with Serum a-Tocopherol Concentrations in African American Adults. J. Nutr. 137: 2297–2303, 2007.

9. Gibson S, Ashwell M. Dietary patterns among British adults: compatibility with dietary guidelines for salt/sodium, fat, saturated fat and sugars. Public Health Nutr. 2011 Aug;14(8):1323-36. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011000875. Epub 2011 May 6.

10. T. R. Kirk. Role of dietary carbohydrate and frequent eating in body-weight control.

Proceedings of the Nutrition Society (2000), 59, 349–358

To snack or not to snack – satiety and weight management

Snacking and satiety

We eat a meal, and hunger gradually builds up until the next eating occasion. There has been a wealth of research on whether people tend to compensate for the energy intake of a snack, and there is some evidence to suggest that feelings of hunger are reduced at a subsequent meal when you eat a snack (11-16).

A high-protein snack may also delay the request of the subsequent meal compared with a high carbohydrate snack. Research has shown a reduction in food intake after a high-protein snack compared with a high-fat or carbohydrate-containing one when a meal is given at a set time (17-18). These appetite effects are possibly due to lower insulin secretion after the high protein snack (19).

Research is also looking at the ideal time delay between a satisfying snack, such as a protein-rich yogurt, and a subsequent meal to optimise the snack’s effects on energy intake. The delay must be long enough to allow the optimal impact of satiety mechanisms but not so long that any energy intake benefits are overridden at that next meal. A systematic review of preload (meal, snack, beverage) studies, found that energy compensation was maximized when the preload was in semi-solid or solid form and the inter-meal interval was between 30–120 min (20).

There is evidence that familiarisation with the satiety effects of foods can positively influence portion sizes and energy intake, reinforcing the benefits of regular planning and consumption of a familiar satisfying snack (21).

Snacking and your weight

Snacking often conjures up feelings of guilt and a fear of weight gain. However, the current balance of evidence indicates no clear association between snacking, weight gain and obesity. For example, observational studies have shown positive associations (22, 23, 24), inverse associations (25-30) or no association between snacking and bodyweight (5, 31-34).

References:

11. de Graaf C. and Hulshof T.. Effects of Weight and Energy Content of Preloads on Subsequent Appetite and Food Intake. Appetite, 1996, 26, 139–151

12. Speechly DP, Buffenstein R. Greater appetite control associated with an increased frequency of eating in lean males. Appetite. 1999 Dec;33(3):285-97.

13. Johnstone AM1, Shannon E, Whybrow S, Reid CA, Stubbs RJ. Altering the temporal distribution of energy intake with isoenergetically dense foods given as snacks does not affect total daily energy intake in normal-weight men. Br J Nutr. 2000 Jan;83(1):7-14.

14. Carlson O, Martin B, Stote KS, Golden E, Maudsley S, Najjar SS, Ferrucci L, Ingram DK, Longo DL, Rumpler WV, Baer DJ, Egan J, Mattson MP. Impact of reduced meal frequency without caloric restriction on glucose regulation in healthy, normal-weight middle-aged men and women. Metabolism. 2007 Dec;56(12):1729-34.

15. Leidy HJ, Campbell WW. The effect of eating frequency on appetite control and food intake: brief synopsis of controlled feeding studies. J Nutr. 2011 Jan;141(1):154-7. doi:

10.3945/jn.109.114389. Epub 2010 Dec 1.

16. Allirot X., Saulais L., Seyssel K., Graeppi-Dulac J., Roth H., Charrié A., Drai J., Goudable J., Blond E., Disse E., Laville M.. An isocaloric increase of eating episodes in the morning contributes to decrease energy intake at lunch in lean men. Physiology & Behavior 110–111 (2013) 169–178

17. Porrini M, Santangelo A, Crovetti R, Riso P, Testolin G, Blundell JE. Weight, protein, fat, and timing of preloads affect food intake. Physiol Behav. 1997 Sep;62(3):563-70.

18. Poppitt SD, Swann DL, Murgatroyd PR, Elia M, McDevitt RM, Prentice AM. Effect of dietary manipulation on substrate flux and energy balance in obese women taking the appetite suppressant dexfenfluramine. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998 Nov;68(5):1012-21.

19. Marmonier C., Chapelot D., Fantino M., Louis-Sylvestre J.. Snacks consumed in a nonhungry state have poor satiating efficiency: influence of snack composition on substrate utilization and hunger. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:518–28.

20. Almiron-Roig E., Palla L., Guest K., Ricchiuti C., Vint N., A Jebb S., and Drewnowski A. Factors that determine energy compensation: a systematic review of preload studies. Nutr Rev. 2013 Jul; 71(7): 458–473.

21. Brunstrom JM, Collingwood J, Rogers PJ. Perceived volume, expected satiation, and the energy content of self-selected meals. Appetite. 2010 Aug;55(1):25-9. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.03.005. Epub 2010 Mar 19.

22. Bertéus Forslund H, Torgerson JS, Sjöström L, Lindroos AK. Snacking frequency in relation to energy intake and food choices in obese men and women compared to a reference population. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005 Jun;29(6):711-9.

23. McCarthy SN, Robson PJ, Livingstone MB, Kiely, M, Flynn A, Cran GW, Gibney MJ. Associations between daily food intake and excess adiposity in Irish adults: towards the development of food-based dietary guidelines for reducing the prevalence of overweight and obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006 Jun;30(6):993-1002.

24. Howarth NC, Huang TT, Roberts SB, Lin BH, McCrory MA. Eating patterns and dietary composition in relation to BMI in younger and older adults. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007 Apr;31(4):675-84. Epub 2006 Sep 5.

25. Basdevant A, Craplet C, Guy-Grand B. Snacking patterns in obese French women. Appetite. 1993 Aug;21(1):17-23.

26. Summerbell CD, Moody RC, Shanks J, Stock MJ, Geissler C. Relationship between feeding pattern and body mass index in 220 free-living people in four age groups. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1996 Aug;50(8):513-9.

27. Titan SM, Bingham S, Welch A, Luben R, Oakes S, Day N, Khaw KT. Frequency of eating and concentrations of serum cholesterol in the Norfolk population of the European prospective investigation into cancer (EPIC-Norfolk): cross sectional study. BMJ. 2001 Dec 1;323(7324):1286-8.

28. Ma Y, Bertone ER, Stanek EJ 3rd et al. (2003) Association between eating patterns and obesity in a free-living US adult population. American Journal of Epidemiology 158: 85–92.

29. Snoek HM, van Strien T, Janssens JM, Engels RC. Emotional, external, restrained eating and overweight in Dutch adolescents. Scand J Psychol. 2007 Feb;48(1):23-32.

30. Keast, DR, Nicklas, TA, O’Neil, CE. Snacking is associated with reduced risk of overweight and reduced abdominal obesity in adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999-2004. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 92: 428-35.

31. S. Whybrow and T. R. Kirk. Nutrient intakes and snacking frequency in female students. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics Volume 10, Issue 4, pages 237–244, 1997-08

32. Hampl JS, Heaton CL, Taylor CA. Snacking patterns influence energy and nutrient intakes but not body mass index. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2003 Feb;16(1):3-11.

33. Nicklas TA, Morales M, Linares A et al. (2004) Children’s meal patterns have changed over a 21-year period: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 104:753–61.

34. Kerr M & McCaffrey T (2007) Evaluation of snacking behaviour in children and adolescents: associations with body composition, physical activity and risk of obesity. Project N09020. Final report to the Food Standards Agency

The healthy snack, definition and recommendations

There is currently no consensus on the definition of ‘snacking’ and this is reflected in the wide variations in snacking study design. The lack of a clear definition has been repeatedly highlighted as a barrier to evidence-based dietary recommendations for consumers (35). Despite this fact, a healthy snack should:

- Contribute to nutrient intake to help ensure adequacy is obtained

- Allow for variety, which will increase pleasure and help consume a variety of essential nutrients

- Be composed in such a portion size that so that calories, fat, sodium and added sugar are not over-consumed

- Be enjoyed mindfully

- Leave you feeling full and satisfied

- Have a positive physiological effect, e.g. cognitive performance, energy for activity

If planned properly, healthy snacking can help build a nutritious diet!

Many country-specific recommendations focus on the choice of snacks rather than frequency of consumption (36).

Snacking or eating frequency is not defined in these recommendations. However, dental-related guidance often recommends limiting the frequency of eating occasions of foods and drinks containing fermentable carbohydrate to 5-6 occasions per day (37).

In Sweden, the recommendation is more specific, with 1-3 snacks advised per day. The UK Food Standards Agency recommends snacks contribute to 20% of daily energy intake in their guidance for institutional meal planning (39).

Food and nutrient needs of individuals vary depending on many individual factors, including age and activity level (40). Therefore the importance of snacking can vary accordingly, which makes it difficult to standardize recommendations.

References:

35. Guy H. Johnson & G. Harvey Anderson (2010) Snacking Definitions: Impact on Interpretation of the Literature and Dietary Recommendations, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 50:9, 848-871, DOI:10.1080/10408390903572479

36. US: Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010 (USDA), Australia: Australian Dietary Guidelines, 2013, France: Programme National Nutrition Santé, 2011.

37. Duggal MS, et al. Enamel demineralisation in situ with varying frequency of carbohydrate consumption with and without fluoride toothpaste J Dent Res (2001) 80: 1721-1724; EUFIC 2006).

38. Livsmedelsverkets National Food Administration Sweden, rapport nr 20/2005, Swedish Nutrition Recommendations Objectified (SNO)

39. Food Standards Agency, FSA nutrient and food based guidelines for UK institutions, 2007

40. Wernette et al. 2012, Signaling Proteins that Influence Energy Intake may Affect Unintentional Weight Loss in Elderly Persons, Journal of the American Dietetic Association

What makes yogurt a healthy snack?

It’s packed with nutrients!

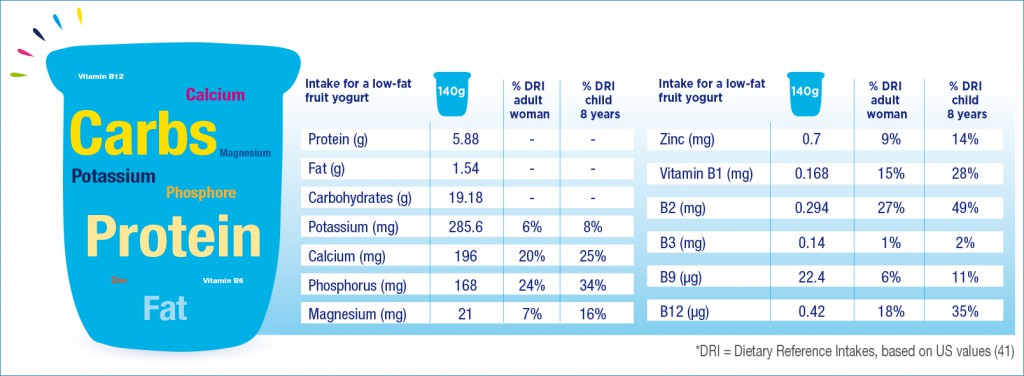

Yogurt provides more than just calcium. Most 8 ounce/225g servings in US and 140g in EU are sources of calcium, phosphorus, and riboflavin, and provide smaller but valuable amounts of a range of other micronutrients.

Can yogurt affect your “brain power”?

In a study some years ago comparing the impact of a yogurt snack to a diet soft drink on cognitive performance, the yogurt snack improved the subjects’ capacity to solve arithmetic problems, and less time was needed to solve these problems (43). Additional studies need to be done to build on this research.

Yogurt and health

A recent study by Zhu and colleagues (44) reported that frequent yogurt consumption (once per week) was associated with better diet quality and insulin sensitivity in children compared to infrequent consumers. Wang et al (45) found that yogurt consumption in adults was associated with lower levels of circulating triglycerides and glucose, lower systolic blood pressure, lower insulin resistance and a healthier diet pattern compared to non-consumers.

Quality counts

Milk and yogurt are excellent sources of high quality protein (contain all 9 essential amino acids in the proportions that cells need for protein synthesis). The protein content of yogurt is generally higher than that of milk because of the addition of non-fat dry milk during yogurt production. Further, when natural yogurt is strained, it is higher in protein weight for weight compared to non-strained yogurt. Proteins in yogurt have been found to be more digestible than proteins in unfermented (standard) milk. (46)

References:

42. McCance and Widdowson’s The Composition of Foods integrated dataset, FSA, 2002

43. Kanarek RB, Swinney D. Effects of food snacks on cognitive performance in male college students. Appetite. 1990 Feb;14(1):15-27.

44. Zhu Y1, Wang H, Hollis JH, Jacques PF, The associations between yogurt consumption, diet quality, and metabolic profiles in children in the USA. Eur J Nutr 2014

45. Wang H, Livingston KA, Fox CS, Meigs JB, Jacques PF, Yogurt consumption is associated with better diet quality and metabolic profile in American men and women, Nutr. Res 2013)

46. Adolfsson O, Meydani SN, Russell RM. Yogurt and gut function. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004; 80(2):245-56.

The sugar story

There is often concern about the healthiness of snack foods with added sugar. However, the overall nutrient density and benefits of the snack needs to be considered. For example, the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) state the following:

- Added sugars are best used to increase the palatability of nutrient dense foods.

- Plain low-fat and fat-free milk and yogurt, as well as flavoured versions containing moderate amounts of sugar, can help Americans get the recommended servings of dairy per day, while staying within daily calorie limits to help maintain a healthy weight.

A recent paper by the American Academy of Pediatrics (47) suggested that nutritional value, portion size and overall diet quality are more effective methods of improving eating habits in children than focussing on elimination of added sugars. A little bit of sugar can help children to enjoy nutrient-rich food and drinks.

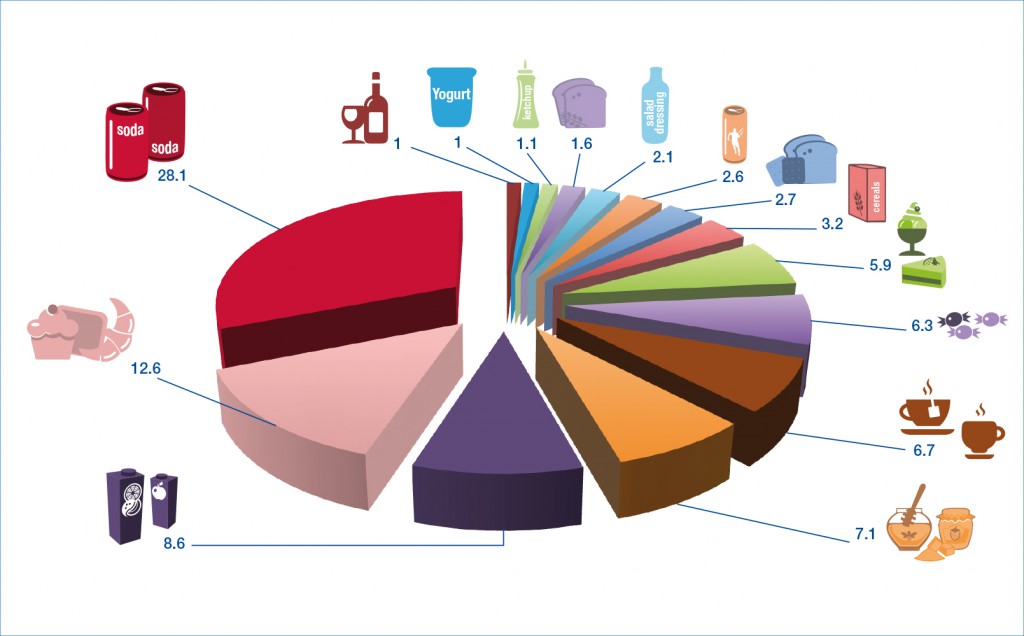

A NHANES analysis of added sugars in children’s diets found that flavoured yogurt contributes about 1% of added sugars to the diets of adults. In comparison, soft drinks contributed 28.1%. (48)

In general, sugar intakes need to be limited for good health. But, sugar makes food tasty! Small amounts as part of an overall healthy diet and lifestyle are perfectly acceptable. What’s important here is the matrix within which sugar is present: sugar in cakes and biscuits typically brings fewer nutrients than sugar in a pure fruit compote, or fruit yogurts.

In addition, in a recent study, El Khoury et al found that a strawberry yogurt with the same calories had a better palatability than plain yogurt and that this did not affect post-prandial blood glucose concentration and subsequent energy intake (49).