For our online symposium « Eating to protect our health and our planet », we asked Lori Shemek to cover Pieter van’t Veer’s talk for us. Dr. Shemek holds a Doctorate in Psychology; she is a Certified Nutritional Consultant and a Certified Life Coach. Follow her on Twitter: @LoriShemek

I am honored to review the June 2, 2020 symposium Eating to Protect our Health and Planet sponsored by Yogurt In Nutrition that includes research presentations by Janet Ranganathan, Prof Pieter van’t Veer and Jess Haines, PhD.

The need to shift to more sustainable diets and food systems that have less of an environmental impact is of increasing concern, but how to ensure that the public supports this transition?

To help us understand more, I am summarizing Dr. Pieter van’t Veer’s research presentation entitled Healthy and Sustainable Diets. Pieter van’t Veer, is a Professor, Chair Nutrition, Public Health and Sustainability at the Wageningen University and Research. He actively links nutrition and public health to environmental sustainability. He eloquently summarizes what we can learn from modeling studies for sustainable diets.

Dr. van’t Veer states that not only is our current global diet undernourished but adding in the element of unsustainable food systems creates a complex global situation.

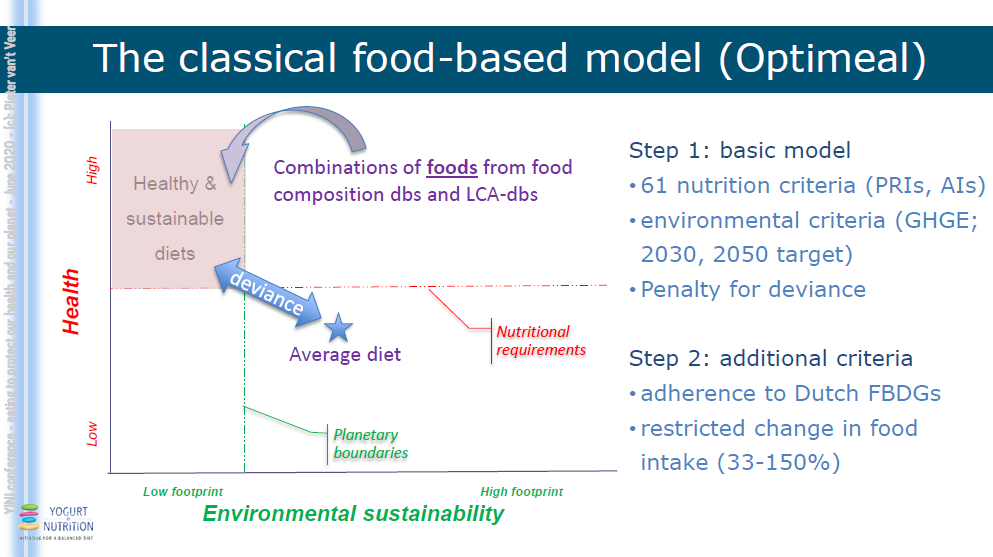

Dr. Van ‘t Veer admits that a change to a global sustainable, healthy diet is not an easy task and essentially unrealistic when we do not take into account the consumer’s vital acceptability. Yet he says it can be accomplished using two modeling techniques he presented: The classical food-based model Optimeal and SHARP both are software programs to help design the optimal diet in each country that will have less GHGE and yet be nutrient-rich and with consumer acceptability. I will be explaining these two models more in-depth later in the article, as guides to achieve these challenges of a healthier planet and population with diets, that as mentioned, are part of the prevailing culture.

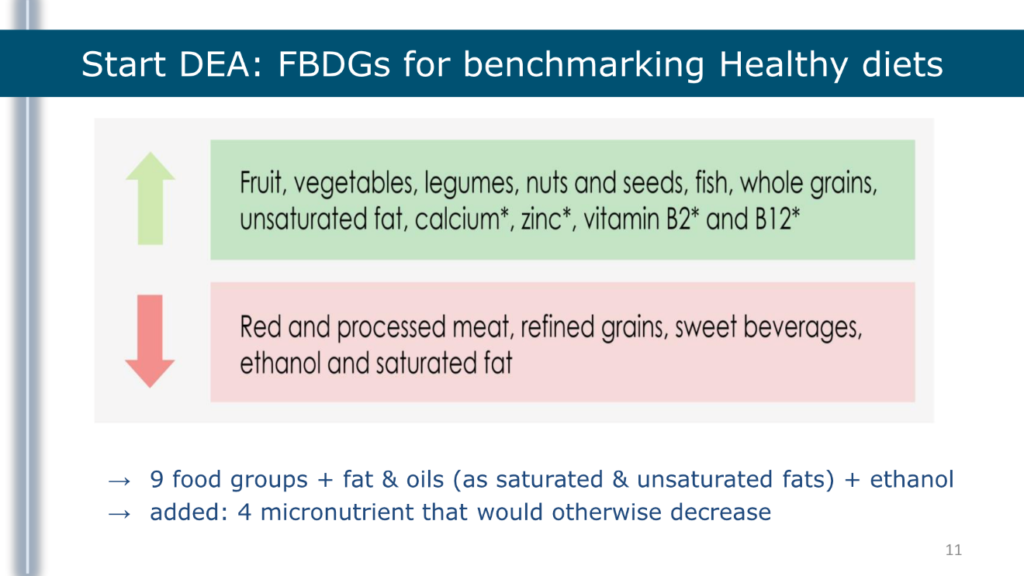

To grasp the task more fully, it is of key importance to note that Food-Based Dietary Guidelines (FBDG) is used as a benchmark with the Optimeal or Sharp models.

By limiting red meat, refined grains, sweet beverages etc. we are not only promoting better health but increasing the nutrient-density and palatability of the diet while decreasing the C02 footprint. However, increasing fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, fish, some dairy and specific added nutrients will reduce our GHGE and improve health outcomes at the same time.

What is the Eat-Lancet report ?

One quarter to a third of our total CO2 footprint comes from food. With this in mind, the Eat-Lancet Commission provided some Recommendations for a more sustainable diet:

- Optimal Caloric Nutrition

- Include Diversity of Plant-Based Foods

- Limited Animal-Sourced Foods

- Limited Refined Grains and Highly Processed Foods

- Doubling Fruits, Vegetables, Legumes and Nuts

By adhering to a diet such as this, greenhouse gas emissions worldwide would be reduced to about 50% compared to the Business as Usual (BAU) Eat-Lancet.

Is the Eat-Lancet report the solution to reducing our global footprint?

The proposal of this commission is that food production promotes a high level of C02 worldwide and shifting to plant-based diet would have massive benefits. However, Van ‘t Veer explained that removing drastically animal protein from the diet, which animal protein alone creates a large GHGE footprint, would have serious nutritional consequences for world health as animal protein provides important key micro-nutrients such as calcium, iron, zinc and all essential amino acids, including vitamin B12 – there would be a reduction in nutrients. Although global food production is feeding millions worldwide with refined foods, sugar and more, the average diet is still extremely low in key nutrients. This inadequate nutrition has led to poor health worldwide that includes heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, obesity and higher morbidity and mortality.

Incorporating the main tenets of the Eat-Lancet diet to reduce future environmental impact, means we need to extrapolate the Eat-Lancet tenet’s overall recommendations to national and cultural boundaries where human actions have become the main driver of global environmental change. It is the consumers who ultimately make the choices as their acceptability ultimately dictates changes.

What are these Optimal Models and how can the help us?

Dr. van’t Veer states that data and models are necessary to design this dietary transformation.

As mentioned, Dr. van’t Veer’s presented the models Optimeal and SHARP that allow us to see the potential impact of a healthy diet on the environment. We know that Data is a key component in diet design, that includes C02 reduction.

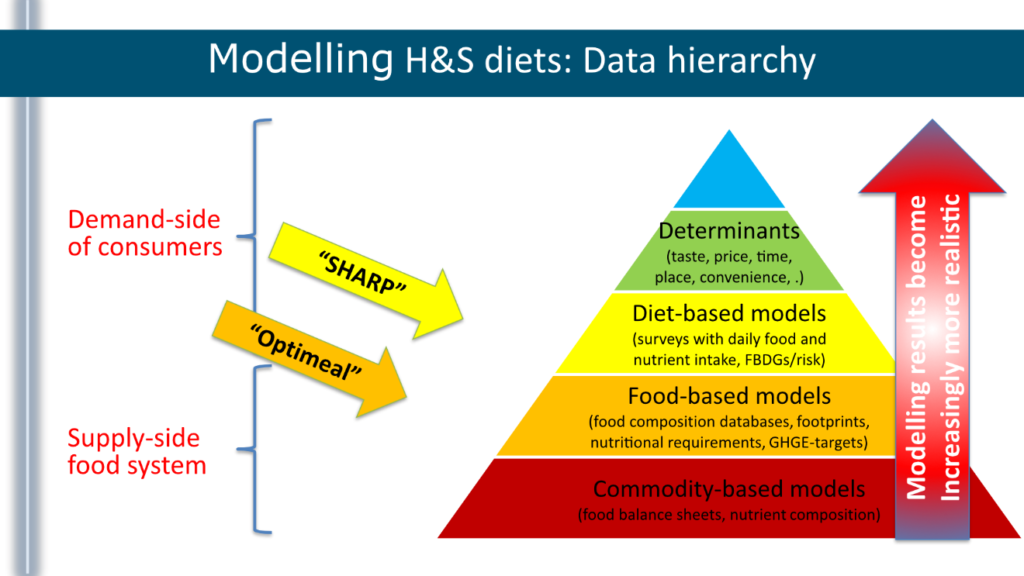

When you go from the bottom to the top of the hierarchy towards the Demand-side of the consumer, results become much more realistic from the consumer point of view.

The Supply-side Food System contains commodity-based models that incorporate food balance sheets and nutrient composition (typically using energy and protein) and demand-side of the consumers. Further up the hierarchy are Food-Based Models that use a much more refined nutrient composition than commodity-based models. Also included are footprints and GHGE.

On the Demand-side of consumers in the hierarchy, nutritional surveys are calculated and food-based dietary guidelines to offer a direction of change to the models. Developing these types of models further, adding determinants such as taste, price, time, place, convenience etc. because these factors always play a prominent role in consumer food choice.

Within the Food-Based Models, Dr. Van’t Veer uses Optimeal (classical) and for the Diet-Based Models, he uses the SHARP model – is an acronym for: Sustainability; Health; Affordability; Reliability and Preferability.

Both Optimeal and SHARP models also indicate that dairy fits well into a healthy and sustainable diet due to the high concentration of nutrients per portion and results in lower Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHGE) – Pieter van’t Veer, June 2020

In the SHARP model, protein sources shifted from red and processed meat to either eggs, fish or dairy. Depending on the country, liquid dairy increased to 105-145%, cheese changed to 77-122% of current intakes.

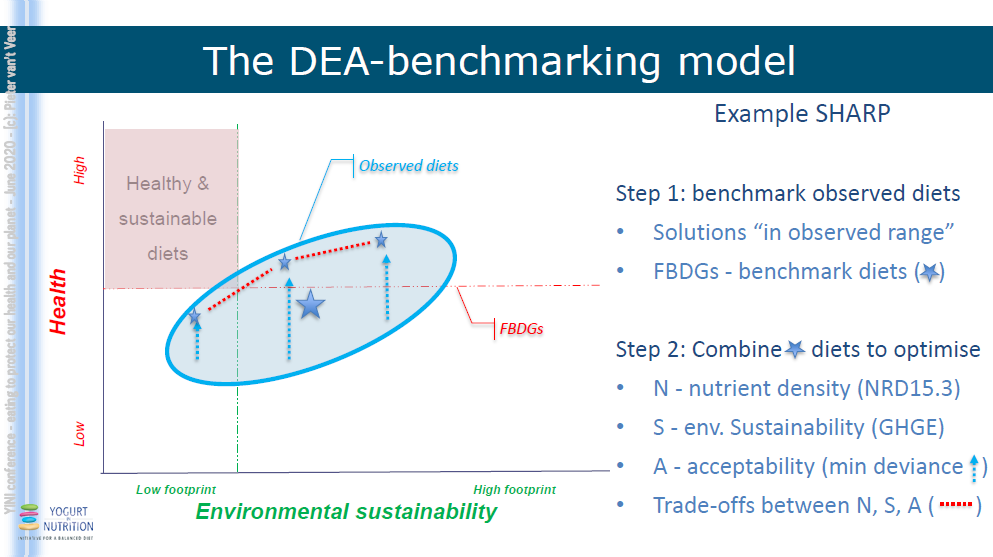

The DEA model, a benchmark approach (Data Envelopment Analysis, DEA) includes SHARP that uses a set of current diets as opposed to foods via the MP model where you create a combination of foods to make a diet (versus combining diets to achieve a calculated diet). DEA is interesting as it includes currently acceptable cultural diets via the population. Using the SHARP DEA Model, the benchmark is observed diets using FBDG that are culturally acceptable. Healthful diets that are not yet environmentally very sustainable.

Using the EAT-Lancet which is also referred to as the ‘Planetary Health Diet’ (very close to the Mediterranean Diet) that calls for a 50% reduction in global consumption of red meat and sugar, and an over 100% increase in nuts, fruits, vegetables, and legumes, by 2050, has been touted as outdated by many as we know that some saturated fat is healthy for cellular health, hormone health and more.

In describing the OPTIMEAL Model, it is a classic food-based model using nutritional criteria adding in environmental criteria, creating a healthy and sustainable diets. This should be as close to what people are used thereby avoiding any deviance. If there is any deviance, reconsideration is necessary using additional criteria such as ensuring that the diet truly adheres to FBDG criteria, restriction in food intake etc.

FBDG Benchmarking Guidelines include an increase in fish, nuts, seeds, legumes, whole grains, unsaturated fat, liquid milk slightly and the micronutrients calcium, zinc, B2, B12 and a decrease in red and processed meat, refined grains, sweet beverages, alcohol and saturated fat.

The impact on Greenhouse Gas Emissions – is it Realistic?

To meet the GHGE-target, an example would be much more plant-based foods and much less animal protein. Potential further restrictions that would include marked reduction in dairy and zero animal protein. This is not recommended, as nutritionally it is not realistic from a consumer compliance perspective and it lacks diversity. Simply adding in more meat and dairy creates acceptability with the consumer and promotes an improved carbon footprint. This is different from the MP in Optimeal, where here only nine food groups are considered along with fats, oils, alcohol and added four micronutrients that would otherwise be lacking.

With the SHARP model, you reduce greenhouse gas emissions maximize sustainability while simultaneously increasing nutrient density. Eat-Lancet diet benchmark showing alone, its ability to markedly reduce GHGE. If the EU-benchmark diets were used, a 31 percent decrease in GHGE.

Both models shift from animal to plant-sourced foods with the Optimeal model showing less animal-sourced foods. The SHARP model suggests less alcohol and sweet drinks would be a more realistic option. Liquid dairy increased in the SHARP model and slightly reduced in Optimeal. However, both models show dairy to be a part of healthy and sustainable diets due to their nutrient richness and lower GHGE footprints, as compared to other animal-sourced products.

Cultural diets play a key role along with consumer acceptance and food based dietary guidelines (FBDG) which then shifts the models closer when added to Optimeal.

Dr. van’t Veer indicates that Optimeal is important to setting goals for population averages. He states that acceptability, being a key feature can easily be incorporated. The SHARP model is an excellent tool that can be utilized as advice within the eating culture.