It’s not just our own diet that we need to change to tackle climate change; it should also be interesting to think about what cows are eating, scientists say. In particular, what about putting them on a diet that makes them burp less?

Cows might look like innocent bystanders in the rural ecology. In fact, as they contentedly munch away, they’re constantly belching out one of the most damaging of greenhouse gases: methane.

So, the challenge is on to figure out how to make cows more environmentally-friendly. Cutting down on their methane emissions promises to combat global warming and slow climate change. In a review of the evidence so far, researchers have identified knowledge gaps to help governments, farmers, and industry to set goals for a sustainable future (1).

How do cows make methane?

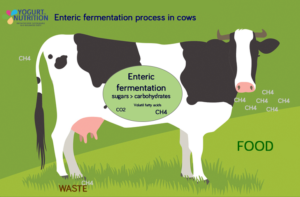

It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that gases emitted by cows come out of their rear end. In fact cows release almost all of their methane by belching it out. That is because cows are ruminants – along with sheep, goats and giraffes, they have a specialised digestive system that allows them to break down grass and other vegetation that can’t be digested by people and other non-ruminant animals (2). Rather than having one stomach like humans, ruminants have four chambers in their stomach. The first of these is the rumen which acts as a fermentation chamber which ‘brews up’ the food after it’s swallowed by the cow. The cow later regurgitates the partially-digested food and chews on it for a while to help finish the job of digesting it – ‘chewing its cud’.

Fermentation is made possible because the rumen is host to a vast number of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi and protozoa, all of which contribute to the harvesting of food energy and provision of nutrients to the cow. Some break down complex carbohydrates into simple sugars, while others break down the cellulose in plant cell walls.

As a by-product of the fermentation process, they produce gases: carbon dioxide and methane. Thea amount of methane cows release depends on their feed. A cow can emit up to an incredible 500 litres of methane each day.

How do dairy cattle contribute to global warming?

Along with carbon dioxide, methane is the most important of the greenhouse gases (GHG), and since 1950, its concentration in the atmosphere has leapt by an alarming 70% (3). Although natural wetlands contribute to methane emissions, 60% come from human activities, including growing rice and keeping ruminant animals such as cattle.

Animal husbandry accounts for 14.5% of world GHG emissions – which is about the same as the transportation industry (4). The fermentation process in the rumen provides more than 90% of methane emissions from livestock and 40% of farm GHG emissions (5).

How is methane from cows measured?

The first step in tackling the cows’ gassy problems is to work out the best way of measuring the methane they emit. A reliable method means that techniques to cut methane emissions can be evaluated and compared. These should be portable methods that don’t disrupt the cow’s routine.

Although there’s no way of sampling whole herds at a time, several technologies, such as a respiration chamber, are being developed to measure methane emissions by individual dairy cows. One that is showing great prospects is a ‘sniffer’ or breath-sampling technique.

Can we reduce greenhouse gas from cows?

What cows eat has a profound effect on how much methane they produce:

- Digesting hay and grass, for example, produces more methane than grain.

- The addition of grain to cows’ feed changes acidity in the rumen and decreases methane generation.

However, the use of high-grain diets must be weighed against the expense of feed production, fertiliser, and machinery use, all of which use fossil fuels.

That’s why scientists are studying alternatives and supplements to cow feed that may produce less methane without leaving a big carbon footprint.

Whichever are found to be the best, it seems that taking time over a leisurely meal makes for a happy cow. Longer rumination times boost milk output and are linked to reduced methane emission in dairy cows.

A salad of seaweed ?

It may not be the first thing that springs to mind when considering cow feed but seaweed is packed full of nutrients and some types contain bromoform – an agent that blocks methane generation. Research has found that methane emission can be more than halved when the bromoform-containing red seaweed Asparagopsis is added to the feed of dairy cows, with no residue found in milk (6).

Further studies on seaweed are needed to ensure that its addition to cow feed is safe for human health, say the authors.

A cup of tea for cows?

Maybe not in a cup, but tea, yucca, and gypsophilla are among the many plants that contain naturally occurring detergents called saponins. These compounds have been shown to decrease methane generation by reducing rumen protozoa, which play a key role in cows’ methane production.

Other plant extracts that are good candidates for boosting our cows’ feed include eucalyptus, garlic, and oregano and white thyme essential oils, and all have been studied for their anti-methane generating activities. Rapeseed oil is another option – scientists found that supplementing diets of nursing dairy cows with rapeseed oil reduced methane emissions by up to 23%.

Methane-cutting measures must be balanced with environmental impacts

Although plant extracts work well in reducing methane emissions, it’s important to make sure the plants can be produced sustainably, taking into account the methods used to harvest, transport, store, and process them into a feed ingredient. The carbon footprint should not outweigh the gains made from methane reduction, the authors warn.

Seaweed holds promise as a sustainable choice because it can be grown in seaweed farms around the world and it is known to absorb vast quantities of carbon dioxide.

Demands on water resources are also important. Cinnamon essential oils, for example, have been shown to reduce methane in lab tests. To produce 1 kg of cinnamon takes 15,526 litres of water and emits 1.6 kg of carbon dioxide, equivalent to driving a car for 6 km (7).

Garlic and oregano tick more boxes when it comes to sustainable production. It takes only 589 litres of water to produce 1 kg of garlic, and 7048 L of water to produce 1 kg of dried oregano (8).

Rapidly-growing plants tend to put less strain on the environment because they need less water and fertiliser than other plants. Eucalyptus trees may be harvested in as little as 3-5 years, making them a quickly renewable resource, with certain kinds of eucalyptus growing 4 m each year, say the authors.

Genetic selection: breeding non-gassy cows

As well as changing our livestock’s diet, we can also look at breeding the right cows.

Scientists believe that genetically selecting low-methane-emitting cows can be a sustainable way to cut emissions from dairy cattle (9). Studies suggest that dairy cows have a low to moderate level of inheritance of their gassy tendencies. Further research is needed to understand the genetics.

The authors point out that, to ensure animal welfare and health, research investigating methane emissions should be conducted in a large number of animals over a long period.

‘To meet future global demands, the livestock industry must investigate natural feed additives that improve nutrient utilization efficiency, provide antibiotic alternatives, and reduce ruminant methane emissions.’ – Bačėninaitė D, et al, 2022

Find out more: read the original article.

Source: (1) Bačėninaitė D, Džermeikaitė K, Antanaitis R. Global Warming and Dairy Cattle: How to Control and Reduce Methane Emission. Animals (Basel). 2022 Oct 6;12(19):2687. doi: 10.3390/ani12192687.

Additional sources:

- (2) Cows, Methane, and Climate Change | Let’s Talk Science (letstalkscience.ca)

- (3) Black, J.L.; Davison, T.M.; Box, I. Methane Emissions from Ruminants in Australia: Mitigation Potential and Applicability of Mitigation Strategies. Animals 2021, 11, 951.

- (4) Kristiansen, S.; Painter, J.; Shea, M. Animal Agriculture and Climate Change in the US and UK Elite Media: Volume, Responsibilities, Causes and Solutions. Environ. Commun. 2021, 15, 153–172.

- (5) Tubiello, F.N.; Salvatore, M.; Rossi, S.; Ferrara, A.; Fitton, N.; Smith, P. The FAOSTAT database of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 015009.

- (6) Stefenoni, H.A.; Räisänen, S.E.; Cueva, S.F.;Wason, D.E.; Lage, C.F.A.; Melgar, A.; Fetter, M.E.; Smith, P.; Hennessy, M.; Vecchiarelli, B.; et al. Effects of the macroalga Asparagopsis taxiformis and oregano leaves on methane emission, rumen fermentation, and lactational performance of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 4157–4173.

- (7) Marie, A. Cinnamon Benefits + Side Effects. HEALabel. 2022.

- (8) Marie, A. Oregano Benefits + Side Effects. HEALabel. 2022.

- (9)Lassen, J.; Difford, G.F. Review: Genetic and genomic selection as a methane mitigation strategy in dairy cattle. Animal 2020, 14, s473–s483.